5. Februar 2016

Life sciences issues in Corporate transactions - Part 2

In the second part to 'Life Sciences issues in corporate transactions', published in the January edition of Synapse, Colin McCall discusses the development cycle and the patent cliff and other matters important to the life science sector, including biosimilars, orphan medicines, parallel imports and compulsory licences.

The development cycle and the patent cliff

Intellectual property protection is vital to maximising the benefit of R&D in the life sciences. Technological improvements, especially when embodied in commercial products, tend to be fairly transparent and therefore available to potential competitors. Such competitors can therefore acquire knowledge about new medicinal products within a reasonably short period of time and with a relatively modest R&D effort of their own.

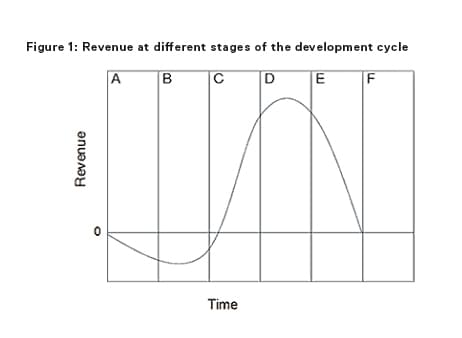

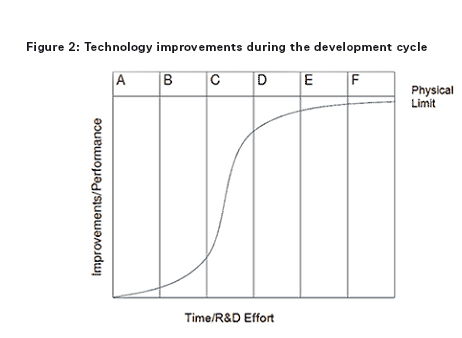

In order to understand the benefit of IP protection and the effect of the ‘patent cliff’, an understanding of the development cycle of a successful medicinal product is important. Early phases in the development cycle, such as discovery and preclinical and clinical phases are typically characterised by initially low but rapidly increasing improvements in the medicinal product (eg, preferred formulations, efficient manufacturing processes, new indications, dosing regimen, etc) as development issues are ironed out, but accompanied by negative total revenue given the huge costs associated with discovery and clinical development. During the intermediate phases of post-marketing approval and then peak sales improvements become increasingly hard to achieve but revenues rapidly increase. In the later stages of generic competition and commoditisation little or no performance improvements are possible and revenues in respect of the product diminish.

In Figures 1 and 2 the columns each represent a phase during the development cycle: A = research (ie, discovery); B = preclinical and clinical phase; C = post-marketing approval; D = peak sales; E = generic competition/product substitution; and F = fully commoditised/obsolescence.

The time at which competition occurs is known as the patent cliff and will depend entirely on the strength of the IP portfolio the initial developer has managed to acquire. When the patent cliff is reached, the revenues available to all market entrants in respect of the product rapidly collapse. But it is the patent holder that loses most. By way of example, the best-selling drug in history, Pfizer's Lipitor had peak sales of around $11 billion per annum in 2009 and 2010 before going off patent in 2011. Since then Pfizer's sales of Lipitor collapsed to $2 billion for 2013. Indeed, in the last five years according to an IMS report1 the patent cliff has caused losses in revenue to innovator pharmaceutical companies of $154 billion.

The costs/revenues shown in the development cycle curve in Figure 1 represent the costs/revenues spent or achieved by all market entrants in respect of a given medicinal product as a whole and not just the costs/revenue of the first life sciences company to develop the new medicinal product. It will be the first developer that incurs almost all of the cost and derives almost all of the revenue up until the patent cliff. Thereafter, the revenues are shared by all market entrants.

The longer a life sciences company can prevent competition and delay the patent cliff, the longer it can prevent price erosion and the greater the proportion of the available revenues from a particular product it can keep for itself. In order for life sciences companies to weather the storm of patent cliff faces they must continually bring new medicinal products to market through a development pipeline. Historically these pipelines have been derived through internal R&D efforts, but increasingly, larger life sciences companies are seeking to bolster their development pipeline with the acquisition of smaller-cap life sciences companies with late-stage development products through corporate transactions or through in-licensing deals. Accordingly, early-stage life sciences companies that have broad IP protection in respect of their core technologies are much more attractive investment propositions.

Other matters of importance in the life science sector

Biosimilars

Improvements in technology and pressures to diversify business models away from small molecule drugs are just two of the factors that are focusing attention on biological medicinal products (ie, medicinal products that are made by a living organism, such as a bacterium or yeast and can consist of relatively small molecules such as human insulin or erythropoietin, or complex molecules such as monoclonal antibodies). This has led to a rise in biosimilars.

Biosimilars are biological medicinal products that are similar to another biological product that has already been authorised and that do not differ significantly from the original product in terms of quality, safety and efficacy. As such, biosimilars are copies of biological medicines that are already approved.

There is no formal definition of ‘biosimilar’ in European legislation and the term biosimilar should not be confused with the terms ‘biobetter’ and ‘me-too biologic’.

A biobetter is a biological product that has been altered structurally or functionally to improve its performance. A me-too biologic is a biological medicine that targets the same pathway but is developed independently of a reference biological and is not compared to it. Neither a biobetter nor a me-too biologic can be authorised using the biosimilar route.

An applicant for approval of a biosimilar product under the biosimilar route is required to demonstrate that its product is similar to a previously authorised product. The application for approval can reference data submitted for the previously authorised product after the expiry of the data exclusivity period.

However, the use of the term ‘similar’ reflects the scientific reality that biological products cannot be copied precisely. Biological products are much larger and more complex than chemical pharmaceutical compounds and are produced in sensitive biological systems that can be affected by small changes in process conditions. Controlling the production of biological products, in particular any post-translational modifications, is therefore challenging. So, while it is possible to control precisely the production of generic chemical pharmaceutical compounds and to authorise them using an abridged procedure on the basis of bioequivalence data, this is not possible with biological products.

Data over and above the standard tests required for small molecule generics will therefore normally be required in order to demonstrate that a biosimilar is comparable to the reference biologic product. As a general rule, the biosimilar route requires more extensive testing and, most likely, clinical trials (which are not needed for small molecule generic drugs).

Orphan medicines

Since the pharmaceutical industry has fewer incentives, under normal market conditions, in developing and marketing medicinal products intended for rare diseases that by definition will only be used to treat small numbers of patients, the EU offers a range of incentives to encourage the development of these medicinal products – known as orphan medicines.

For a medicinal product to be classed as an orphan medicine, it must be intended for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of either:

- a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the EU at the time of submission of the application for orphan designation, or

- a life-threatening, seriously debilitating or serious and chronic condition where, without incentives, it would be unlikely that the revenue after marketing of the medicinal product would cover the investment in its development.

There must also be either no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention or treatment of the condition concerned, or, if there is such a method, the new medicine must be of significant benefit to those affected by the condition.

The principal benefit for medicinal products designated as orphan medicines is that they benefit from more generous treatment as regards market exclusivity, namely:

- a period of 10 years from the date of marketing authorisation, which may run in parallel with the basic marketing exclusivity if the drug is also authorised (via a separate marketing authorisation) for other indications

- any additional orphan indications for the same product will also benefit from their own separate 10-year period of market exclusivity; and where an application for a marketing authorisation for an orphan product includes the results of studies conducted in accordance with an agreed PIP, the 10-year period is extended to a period of 12 years.

Parallel imports

Parallel import regime in Europe

Parallel importation of medicinal products in the EEA relies on the principle of patent exhaustion, which itself arises from the EU's and also the EEA's treaty commitments to the free movement of goods. These freedom of movement of goods rules as regards patented medicinal products were first established in 1974 in the case of Centrafarm BV v Sterling Drug Inc2 and dictate that when a patent/SPC holder puts (or consents to the putting of) a medicinal product on the market anywhere in the EEA, the patent/SPC holder cannot object to a purchaser of those products subsequently putting them on the market in a different EEA member state, regardless of whether such import into a subsequent EEA member state would infringe the patent/SPC holder's national patent/SPC rights in the member state of destination. As a result of the differences in prices set by national governments and also by the patent/SPC owners themselves in the various different EEA states there is now a significant volume of parallel import activity.

The parallel import of medicinal products is, however, subject to significant regulation. The importer still requires a licence to import and market the product in the member state of destination, and the product packaging must meet the requirements of the member state of destination.

Parallel import licences

A parallel imported medicinal product may be distributed under an authorisation obtained through a simpler procedure than that for the initial marketing authorisation for the product. To qualify for the simplified procedure, the parallel imported medicinal product must satisfy two conditions. It must:

- have been granted a marketing authorisation in the member state of origin, and

- be sufficiently similar to a product that has already received marketing authorisation in the member state of destination.

The similarity between two medicinal products is considered to be sufficient when the two products have been manufactured according to the same formulation, using the same active ingredient, and have the same therapeutic effects. A parallel imported medicinal product can also be distributed under the simplified procedure even if the similar product upon which its licence is based is no longer available on the market, provided that public health requirements are met.

Repackaging of parallel imports

Repackaging will be necessary if the packaging sizes in use in the member state of origin are not permitted in the member state of destination. In principle, however, this is precluded by the trademark right of the manufacturer since all changes to the packaging or the product itself will constitute an infringement of the manufacturer's trademark. But this rule conflicts with the principle of the free movement of goods within the EEA. The case of Bristol-Myers Squibb3 has therefore ruled that certain necessary and appropriate changes are permitted, if they are made in order to eliminate obstacles in the distribution process. The so-called BMS Conditions are:

- the use of the trademark right by the owner contributes to the artificial partitioning of the internal market

- the repackaging does not adversely affect the original condition of the product

- it is stated on the new packaging by whom the product has been manufactured and by whom it has been repackaged

- the presentation of the repackaged product is not such as to damage the reputation of the trademark or of its proprietor, and

- the proprietor of the trademark receives written notice of the repackaging before the new product is put on sale and in addition, if he requests it, is supplied with a specimen of the repackaged product upon demand.

The repackaging must be necessary, and not just motivated by commercial interests. For example, repackaging is not justified for a parallel imported product that may be put on sale in the member state of destination simply by changing the labelling of the outer packaging (eg, language matters).

Compulsory licences

The availability of compulsory licences in respect of patents, especially in relation to pharmaceutical patents, has been the subject of considerable attention lately. This is mainly as a result of the Indian courts showing their willingness to grant compulsory licences in respect of pharmaceutical patents. In particular, the Indian courts recently granted a compulsory licence to an Indian generic pharmaceutical company under Bayer’s patent for its cancer drug Nexavar, determining that in essence Bayer’s price for Nexavar was too high. This, together with Bayer’s failed challenge that India’s patent legislation under which the compulsory licence was granted was not compliant with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS agreement puts restrictions on the ability of World Trade Organization members (of which India is one) to restrict the exclusive rights of patentees through – among other things – compulsory licences), has led to significant media interest in the power under national patent legislation to grant compulsory patent licences.

Article 31 of the TRIPS agreement provides that where patent legislation of World Trade Organization member states allows compulsory licences to be granted the following provisions must be included:

- Each case must be decided on its own merits.

- The applicant for the compulsory licence must have made efforts to take a licence from the patentee on reasonable commercial terms.

- The scope and duration of the compulsory licence must be limited to the purpose for which it was granted, such that it may be terminated or amended if the circumstances that led to the grant of the compulsory licence change or cease to exist.

- The patentee must be paid adequate remuneration for use under the compulsory licence.

- The decision to grant a compulsory licence and the determination of what is adequate remuneration shall be subject to judicial review.

- Where a compulsory licence is granted in order to enable a second patent to be exploited, the invention claimed in the second patent must involve an important technical advance of considerable economic significance in relation to the invention claimed in the first patent and the patentee of the first patent must be entitled (on reasonable terms) to a cross-licence in respect of the second patent.

This article is an extract from the Life Sciences chapter of Intellectual Property Issues in Corporate Transactions, published by Globe Law and Business, December 2015.

If you have any questions on this article or would like to propose a subject to be addressed by Synapse please contact us.

1 Report by the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, Global Outlook for Medicines Through 2018, November 2014.

2 15/74.

3 Joined cases C-427/93, C-429/93 and C-436/93.

Related Insights

Word on the street at the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference 2024

von mehreren Autoren

Word on the street at the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference 2023

von mehreren Autoren

Edison Open House Global Healthcare 2021 – key takeaways from our panel

von mehreren Autoren