- Home

- News & Insights

- Insights

- New guidance on righ…

7. August 2025

RED Alert - Summer 2025 – 7 von 7 Insights

New guidance on rights of light claims: Waldram is still the correct approach… for now

- Quick read

Welcome to the third edition of RED Alert of 2025.

Also featuring in this update:

- Pulling the plug on insurance profits: Why landlords can’t bank on commission

- Remediation round-up: recent cases provide clarity on the application of Building Safety Act 2022

- Proposed changes to business tenancies: ban on upwards-only rent reviews

- Secure in its (provisional) conclusions: the Law Commission issues interim statement for 1954 Act Reform

- The Renters' Rights Bill: when will it come into force?

- Court of Appeal upholds developer liability in Triathlon Homes: a landmark Building Safety Act decision

The recent judgment in Cooper (C) v Ludgate House and Powell (P) v Ludgate House [2025] EWHC 1724 (Ch) has provided some guidance for developers and owners of property adjacent to the development site on the court's approach to determining the impact of loss of light, use of injunctive relief to protect rights of light and the approach to quantifying damages. The judgment gives significant consideration as to how a resolution to permit development pursuant to section 203 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 (s 203) interacts with damages claims for infringement of rights to light.

Facts

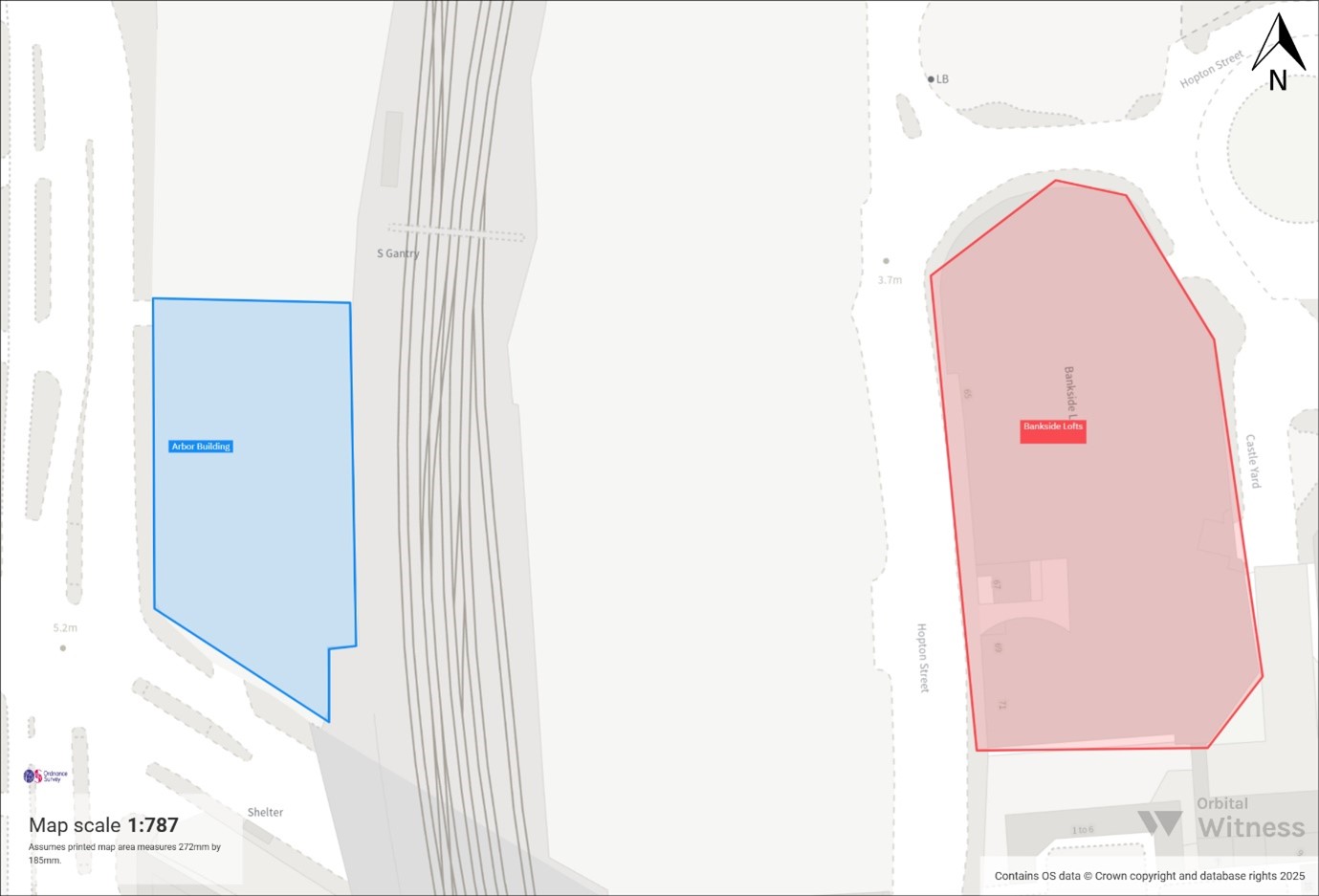

Arbor is a 19-storey office building in Blackfriars, London and is part of a larger development known as Bankside Yards, built above and comprising railway arches constructed in 1864 as part of the original Blackfriars Station. The below plan shows the approximate location of Arbor (in blue) by reference to C and P's properties in Bankside Lofts (in red).

Photo credit: Orbital (https://www.orbital.tech/)

The development site is in two parcels, owned by different entities, but under joint development (and in this article we refer to the owners of the land as the developer for convenience). Part of the development site was subject to a s 203 resolution which defeats easements including those of rights of light over the subject land, although this resolution did not extend to the Arbor building land (the s 203 Land). Arbor impacted on the light enjoyed by various neighbouring properties, whose owners asserted claims against the developer, most of which were settled for payment of damages. C and P did not settle their claims and brought proceedings against the developer in nuisance, claiming that their rights to light had been infringed by the development of Arbor and that the developer ought not to have continued with construction of the building once their claims were asserted. They sought an injunction requiring the demolition or cut back of Arbor, or alternatively, damages.

An important feature of the case was that whilst Arbor presented an interference with rights of light to C and P's properties, the demolition of an adjacent building meant that C and P's properties temporarily enjoyed improved light to their properties, mitigating the impact of the Arbor building on their enjoyment of light although the future development of the rest of the Bankside Yards site, including the s 203 Land would, together with Arbor, reduce their enjoyment of light.

The effect of light enjoyed over the s 203 Land

The parties disagreed as to how to approach the loss caused to C and P's properties. One dispute was how to approach the impact of the s 203 Land on C and P's properties, and whether the loss of light caused by the development of the s 203 Land and statutory compensation due to C and P should be considered or disregarded when assessing any loss to C and P caused by Arbor.

- The developer argued there would be double recovery if the impact of the s 203 Land and statutory compensation was disregarded, as C and P would have the right to seek statutory damages in respect of the s 203 Land when it was built upon.

- The court rejected this argument because it considered any loss in respect of the Arbor parcel and the s 203 Land to be separate. Further, as the developer had voluntarily invoked the statutory regime over the s 203 Land, which meant that C and P could not object to the loss of that light and because the statutory compensation would be compensating for a different loss, it should be disregarded.

- The developer also argued that the two development parcels (the Arbor site and the s 203 Land) were separate parcels of land in different ownership and this enabled the court to take into account that:

(i) C and P had the benefit of the temporarily improved light from the s 203 Land; and

(ii) their right to compensation which should have the impact of reducing the 'Arbor claim' by sharing the impact of the loss over the two parcels of land. - The court rejected this and considered that the two parcels of land were effectively in common ownership and being jointly developed so should be considered together. It held that the s 203 Land was to be disregarded when assessing any loss to C and P principally because the light from this parcel could no longer be protected because of the s 203 resolution, which is a novel point for judicial consideration. The court was concerned that if the s 203 Land light was not disregarded it would transfer all of the burden of the loss to the s 203 Land which the C and P had no ability to protect following the s 203 resolution.

Waldram vs Radiance

Detailed consideration was given to the correct method of assessing loss of light. In a marginal case the court considered that it might be helpful to use alternative methods to assess loss of light, such as the Radiance method, which was advocated for by the developer. Ultimately, the court considered these to be too subjective and held that the Waldram method was the preferred approach. The court heard evidence that most specialist consultants continue to use the Waldram method for initial assessments, reflecting its status as a trusted formula by specialist advisors, asset holders and interested parties. The court clearly recognised that there were limitations to the Waldram method and indeed to the Radiance method and so, at least for the time being, Waldram remains the method to be used when assessing adequacy of light. With constant technological improvements, this may be something that the court revisits in the future.

Approach to injunctive relief

The court approached the question of whether to grant an injunction with care and adopted the balancing exercise established by Coventry v Lawrence. It considered the interests of C and P, whether they could be adequately compensated in damages and whether their motivation was purely monetary (which might have been a bar to an injunction). It noted that the tenants of Arbor had not been joined to the proceedings, and that their position should be considered before an injunction could be implemented. The court did not criticise C and P for delaying taking action as they had acted promptly following the s 203 resolution which significantly changed their position. Planning evidence that if Arbor was demolished then it would be likely to gain a new planning consent to rebuild (or a further s 203 resolution) was accepted. The negative effect on public interest if the building was demolished was also significant. The strong sustainability credentials of Arbor were also considered. For all these reasons, an injunction was not ordered, with damages being a suitable and adequate remedy. Notably, C and P's alternative argument for an injunction which was only implemented if the developer did not redesign the rest of the development to protect their right to light was rejected by the court.

Measure of damages – negotiating damages vs diminution in value

The parties disputed whether diminution in value of C and P's properties or negotiating damages (which considers the profit made by the developer as a result of the part of the building infringing on C and P's rights to light) was the correct measure. The court held that damages for loss of negotiating rights were the appropriate measure of loss and noted that, had this not been the case, it might have tipped the balance in favour of granting the injunction to protect the negotiating position of C and P, as damages might not have been a suitable remedy. The court then proceeded to assess the valuation of the profit and attributed part of the value to C and P's properties, based also on their values. This enabled the court to identify the lost bargaining position and finally, the court then 'stood back' to assess whether the sums to be awarded were justified or not, particularly bearing in mind the value of C and P's properties.

Key takeaways

- The strategy of dealing with rights of light and any compromise for loss of light is vitally important and will be scrutinised by the court when assessing what remedies and damages to award. Evidence of the strategy adopted and advice given may be disclosable in proceedings. Developers may continue to adopt a commercial strategy, even one with risk, but not one that seeks to take advantage of potential claimants.

- Waldron remains the correct approach and principal method of assessing adequacy of and loss of light. Additional methods will require a well evidenced and reasoned analysis if they are to be used.

- When assembling a site for development, thought should be given to the proposed land ownership and how to structure development of each phase alongside considerations as to whether there will be claims for interference with rights of light and possible use of a s 203 resolution, at the earliest opportunity.

- The cost and practicality of joining occupants of the building interfering with light enjoyed by a neighbouring property should be weighed against the need to secure an injunction if this is the preferred outcome. The views of occupants will be taken into account when applying the test to order an injunction.

- Developers should consider whether potential claimants have all the evidence they need to assess whether they should seek injunctive relief when assessing injunctive risk as delay by claimants in seeking an injunction to await the outcome of key information or decisions about the development will not be a bar to relief.

- Public interests are also part of the factual matrix against which to decide whether to grant an injunction, including the public interest in having commercial (and residential) units which provide work opportunities and benefit local businesses / communities, including by the provision of homes.

- Likelihood of obtaining planning permission or a s 203 resolution to reinstate a building which is either cut back or demolished is also a relevant factor to consider when assessing injunction risk.

Developers and adjoining property owners will note that the position remains complex and they should seek legal and professional advice at an early stage of the development process.

In dieser Serie

Secure in its (provisional) conclusions: the Law Commission issues interim statement for 1954 Act Reform

1. Juli 2025

von Rebecca Stephen

Pulling the plug on insurance profits: Why landlords can’t bank on commission

26. Juni 2025

von Emma Archer

Remediation round-up: recent cases provide clarity on the application of Building Safety Act 2022

26. Juni 2025

von Alicia Convery

Proposed changes to business tenancies: ban on upwards-only rent reviews

24. Juli 2025

The Renters' Rights Bill: when will it come into force?

1. August 2025

von Stephen Burke

Court of Appeal upholds developer liability in Triathlon Homes: a landmark Building Safety Act decision

7. August 2025

von Alicia Convery

New guidance on rights of light claims: Waldram is still the correct approach… for now

7. August 2025

von Emma Chadwick

Related Insights

Digital connectivity – New rights for leaseholders?

von Emma Chadwick