What has happened?

- It's relatively rare for claims of infringement of unregistered design right to crop up. However, Edwards v boohoo involves a successful defence by boohoo (the well-known fashion group) of such a claim relating to the design of various items of clothing.

- Design right is the species of design protection unique to the UK. It protects the design of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article. However (unlike all other forms of design), it does not protect surface ornamentation.

- In this particular case, the judge found no infringement as boohoo had not copied any of the claimant's designs. (For some of the claimant's designs and the alleged infringements, see the bottom of this article).

- The case contains some useful learnings for those in sectors such as fashion that sometimes rely on design right, including on the benefits of defining the design precisely.

- It confirms that design right does not subsist in concealed features (such as hidden waistbands) and that the shape/configuration of the design when worn is irrelevant. Finally, the court commented that it is not surprising that new designs sometimes bear a resemblance to previous designs given the number of fashion items produced each week and the fact that there are only so many ways to design clothing to fit the human body.

Want to know more?

Should a design be recorded in a design document?

Design right is governed by section 213 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA). Usually, the design is recorded in a design document with the dimensions specified. However, design right can also arise when an item of clothing (for example) is designed by making the article itself. This is what had happened in this particular case – the designs alleged to be infringed were "recorded" in the clothing items themselves, not a design document.

The court noted the following about this approach:

- This approach can make it easier to establish infringement as the design can be defined by reference to the alleged infringement and described in general terms (as it was in this particular case). It can also be easier to fulfil the test that the alleged infringement is made "exactly or substantially to the design".

- However, this approach – and specifically the approach of defining the design in general terms so that an infringement is caught - can also make it easier for defendants to infringement claims to argue that the design alleged to be infringed (a) is a method or principle of construction which is excepted from design right protection, (b) is invalid for being commonplace, and (c) does not attract design right protection as it's simply an underlying design principle or generalised idea. It can also make it easier for defendants to argue that there is no copying as there are likely to be other sources for the generalised concepts forming the design alleged to be infringed. Arguing these points can provide a "squeeze" on infringement (ie if we infringe, the design is invalid).

Overall, therefore, the court cautioned against defining the design alleged to be infringed in general terms and implied that this could be avoided by drawing up a design document which specifies the dimensions of the design and other original features.

Can concealed features form part of a design?

The court ruled that features that cannot be seen (eg concealed wasitbands) or which are not present (lack of seams and zips) cannot form part of protection for design right.

Is the shape or configuration of a design when worn relevant?

Design right protects features of the shape and configuration of articles such as clothing. The claimant had argued that a design's shape and configuration can vary when worn and that the design as worn is relevant. The court disagreed noting that design right must be clear – the nature of the design cannot vary when worn or according to who is wearing it.

How should infringement be assessed in the fashion industry?

In relation to the infringement, the judge made the following interesting comments:

- It is completely unsurprising that, as a matter of chance, some of the allegedly infringing articles are arguably similar to previous designs given the enormous number of articles of clothing produced each week.

- The stark truth is that there are only so many ways to design clothing to fit the human body.

- The likelihood of a high profile fashion company like the defendant using the claimant's social media feed with few followers published many years ago for design inspiration is low. The opportunity for copying was extremely limited given the relatively small size of the social media following.

- The abstract way in which the claimant has described her designs (so that they are barely original) simply increases the chance that they might resemble other garments designed independently.

What does this mean for you?

- If possible, define designs with specificity (ether up front or when alleging infringement).

- Remember that concealed features and how a design will look on a particular shaped person are likely to be irrelevant.

- For truly original designs, there is definite scope to bring claims of infringement of registered and unregistered designs (including design right).

- Designers should refer to our guidance here on design protection including the options for ensuring that unregistered designs arise in the UK and EU given the specific disclosure requirements.

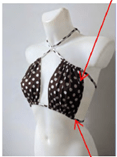

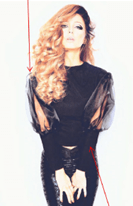

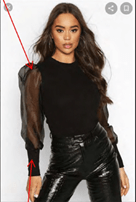

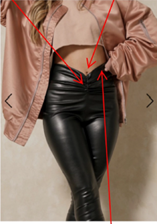

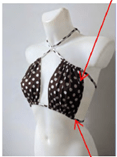

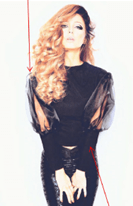

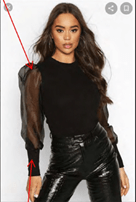

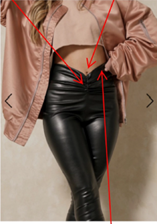

| Design |

Claimant (Sonia Edwards |

Defendant (boohoo) |

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|