- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- In other news

- On this page

25 April 2023

Brands Update - April 2023 – 5 of 5 Insights

In other news

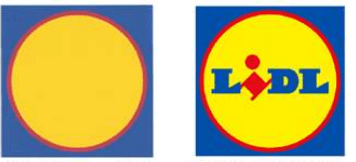

Lidl has won its claim for trade mark infringement against Tesco concerning the latter's use of a yellow circle within a blue square for its Clubcard Prices scheme. Lidl argued that such use infringed its trade mark registrations for a similar logo with and without the word Lidl (depicted below). Lidl was also successful in its claim for passing off and copyright infringement. There was a small victory for Tesco in that it was able to invalidate some of Lidl's trade mark registrations for the wordless mark on the grounds that they were applied for bad faith. However, that did not change the overall outcome. The case is an important one since it further considers the circumstances in which a party might be able to successfully argue bad faith.

The key findings of the court on trade mark infringement were as follows:

- The average consumer would perceive the signs as similar. Visual similarity was the significant feature and the different word elements did not have the effect of extinguishing the strong impression of similarity conveyed by the mark's backgrounds in the form of the yellow circle, sitting in the middle of the blue square. There was evidence that consumers would make the necessary "link" between Tesco's and Lidl's marks.

- Use of the Tesco Clubcard Prices logo constitutes trade mark infringement since it takes unfair advantage of the fame of the Lidl logos and is detrimental to the distinctive character of those logos. Unfair because Tesco would benefit from the value propositions that the Lidl logos convey. Detrimental to distinctive character because Tesco's use of its mark would dilute the uniqueness of Lidl's mark – as evidenced by the fact that Lidl had to take evasive action in the form of corrective advertising.

- Use of the Tesco Clubcard Prices logo also constitutes passing off. A substantial number of Lidl customers would be led to believe that the Clubcard Price is the same as or lower than the price offered by Lidl for the equivalent goods. That mistaken belief would deceive consumers and cause damage to Lidl because price sensitive shoppers would purchase goods at Tesco rather than Lidl.

- Given the degree of similarity between the logos and the fact that Tesco had access to the Lidl logos, the burden of proving lack of copying passed to Tesco. Tesco was unable to discharge that burden. Indeed, there was evidence of copying.

The case illustrates that brand owners need to be careful not to stray too close their competitors' marks even if those marks seemingly consist of relatively commonplace and banal elements. This is particularly so where the mark is well-known. Adding different words – or even a house brand – to a logo might not be enough to avoid a finding of infringement. The similarities between marks must be assessed from the viewpoint of the average consumer (here, a supermarket shopper) – if the average consumer might not focus on the words, then they will not be sufficient to avoid a finding of similarity. Unfair advantage/detriment (or even, confusion) will often follow.

Brand owners must also consider whether they might be liable for copyright infringement where they are using a logo or figurative element. Where that logo or figurative element is closely similar to a third party's work and there has been access to that work, the burden of proving lack of copying will usually shift to the alleged infringer. Having detailed records as to the genesis of a particular mark will be key to rebutting that presumption. The case also illustrates that passing off can be as to equivalence as well as to origin.

Tesco counter claimed that Lidl had no genuine intention to use its wordless marks and that they had therefore been applied for in bad faith. This was on two bases. First, Tesco argued that Lidl had applied for the wordless mark as a defensive weapon, acquired solely to use against others and to widen its monopoly. Secondly, Tesco argued that Lidl had filed successive applications for the wordless mark to circumvent the rules on proving use (so-called ever-greening). Importantly, at an earlier hearing, the Court of appeal had held that the objective circumstances raised in Tesco's pleading were sufficient to create a rebuttable presumption of lack of good faith by Lidl such that it was now for Lidl to provide a plausible explanation of its objectives and commercial logic.

That was achieved by Tesco pleading the combination of (i) the fact of repeat filings with (ii) the assertion that Lidl had had no intention, at the time of filing the original wordless application, of using the wordless mark and (iii) the fact that that Lidl had not in fact ever used the wordless mark. The Court of Appeal also seemed to treat a statement made by Lidl's counsel at the earlier hearing as if it was an admission that the wordless mark was a mere legal weapon. (Counsel for Lidl had accepted that Lidl was indeed seeking broader protection from the wordless mark than it was getting from the logo with the word Lidl, but that it was entitled to seek such protection.) The fact that Lidl's later registrations for the wordless mark covered quite a lot of the goods and services of the original/previous registrations for the wordless mark (and that one later registration for the wordless mark covered every single Class of goods and services) was also relevant. On bad faith, the court held that:

- A finding of actual use is not sufficient to protect against a finding of bad faith. The fact that a registered mark is later found to have been used as a component part of another mark does not (without more) evidence the existence of the necessary intention to use at the time of filing.

- Lidl's evidence and arguments did not address why the wordless mark was originally filed. Likewise, there was no evidence that Lidl knew or thought that it was using the wordless mark by using the mark with text. That the original wordless mark was filed as a legal weapon was therefore a permissible inference from the evidence.

- Lidl was unable to explain why later wordless applications duplicated (at least, in part) the goods and services of earlier applications. That they had been filed to circumvent the rules on proof of use was a permissible inference from the evidence.

- A 2021 registration for the wordless mark survived since there was evidence that, by that point, Lidl genuinely believed that use of the mark with text also constituted use of the wordless mark as well as evidence that the wordless mark enjoyed its own reputation. The fact that there was a 13-year gap in filings for the wordless mark also suggested that Lidl did not have an ever-greening strategy by that point.

The case is consistent with previous rulings on bad faith including the EU General Court's ruling in the Monopoly case. What is interesting is that the burden of proof shifted to Lidl to prove good faith – that was fatal to Lidl and might well be to others who haven’t got records as to why a particular mark was applied for in the past. Lidl did not produce any evidence as to why the wordless mark was originally filed (and then refiled) and so could not discharge this burden. This illustrates the importance of brand owners keeping records of their decision-making process and filing strategies. The case also illustrates that brand owners should not assume that they will be deemed to have filed an application in good faith just because they have subsequently used the mark in question. Where there was no genuine intention to use a particular mark initially (or there is no evidence as to that intention), then refiling for a mark might be appropriate if there is now a desire to put that mark into use. The subsequent application should be deemed to have been filed in good faith even if the earlier one(s) were/are not.

We will report more on the decision and the implications for brand owners in next month's Brands Update.

|

|

| Lidl's wordless and word logos, both registered as trade marks. | Tesco's Clubcard Prices logo. |

The High Court (IPEC) has ruled that Aldi's festive gin-based liqueur, The Infusionist, infringed Marks & Spencer's four earlier UK registered designs for gin globes. M&S's designs consisted of a botanical shaped bottle, stopper, a winter scene (mainly consisting of tree silhouettes) on the entirety of the straight sides of the bottle, a snow effect (on two of the designs) and an integrated LED light in the base of the bottle (on two of the designs).

|

M&S's registered designs 1 and 2. |

Aldi's 'Infusionist' gin liqueurs. |

|

M&S registered designs 3 and 4. |

In holding infringement, the Court paid particular attention to the fact that the designer had considerable design freedom, only one other prior design (forming the design corpus) had a botanic shape and snow effect (but not the other elements of M&S's designs) and that the cumulative similarities between the designs would be striking to the informed user. The court also confirmed that, where a registered design has a priority date, infringement is assessed as at that date.

It is worth noting that M&S filed applications to register the designs in the UK after it had launched its product (within the 12-month grace period) and after Aldi had launched its infringing product. The case shows the value of registered design protection especially for seasonal or short-lived products.

A complex IP dispute about building techniques which has been winding its way through the IP courts has shone a useful light onto an area of passing off law.

A minor issue in the case concerned three domain name variants of “mapletimberframe”, which a defendant had registered. The Court accepted that the claimant owned goodwill in the term and that, on the face of it, use of the domain names would constitute passing off. However, the domain names had not been used during the six years for which they had been registered. Was any remedy available or appropriate?

In the early days of cybersquatting, the Court of Appeal had ruled in the One in a Million case that an interim injunction could be granted to restrain the use of a domain name which had not yet been used because of the threat that it would be used for passing off (a quia timet injunction). This theory relied on the domain name being “an instrument of fraud” and that the name had been registered with the intention of passing off. Some 24 years later, this remains the leading case on the issue.

Here the court decided that there was not a threat of passing off. The domain names had not been used for 6 years and were unlikely to be used now (given the court's finding that such use would be highly likely to constitute passing off). This is useful guidance. The court also declined to order the transfer of the domains to the claimant but the reasoning of this part of the judgement is cursory and less useful. There will undoubtedly be cases where the appropriate remedy would be for the domains to be transferred and so this part of the case should be viewed on the basis of the particular facts.

The case is also interesting for its guidance on the importance of dating assignments of IP rights, which we will consider in the next edition of Brands Update.

The High Court has upheld the UK IP Office's decision that MISTER CHEF is not conceptually similar to MASTER CHEF and there is therefore no likelihood of confusion between the marks. The case is a good example of how lack of conceptual similarity can sometimes be sufficient to avoid a finding of a likelihood of confusion. It also illustrates how the tribunals/courts can focus on one conceptual meaning of a mark (to the exclusion of others) in considering conceptual similarity.

SKA Trading Ltd filed an application to register the mark MISTER CHEF for goods in class 21 (cookware). Shine TV Ltd opposed the application based on its UK and EU trade marks for MASTER CHEF and MASTERCHEF, also covering class 21 (cookware).

The UK IP Office's Hearing Officer had found that the marks were visually and aurally similar to "quite a high degree" but conceptually dissimilar and rejected the opposition. The Hearing Officer considered that the word MASTER in MASTER CHEF / MASTERCHEF would be understood by the average consumer as meaning "a skilled practitioner of a particular art or activity" (as "per the third meaning in the Oxford English Dictionary"). He concluded that, when compared as whole, MASTER CHEF and MISTER CHEF, "have quite distinct meanings."

In its appeal, Shine argued that the Hearing Officer should have considered other meanings of the word "Master" in assessing conceptual similarity. Shine argued that the average consumer would likely perceive the word "Master" as a title used by a boy not old enough to be called "Mr". Taking this meaning into consideration, the Hearing Officer would have concluded that the marks were conceptually similar.

However, the High Court held that it was open to the Hearing Officer to conclude that the average consumer would have had the third meaning of the word "Master" in mind when that word was used in conjunction with the word "chef". Unlike when considering whether a mark is descriptive (and therefore inherently registrable as a trade mark) when all possible meanings are considered, the tribunal/court can focus on one (most likely) meaning when considering whether marks are conceptually similar.

The High Court has upheld a decision of the UK IP Office that a trade mark registration for DELTA for hotel and related services is confusingly similar to, and takes unfair advantage of, prior registrations for DELTA for air transportation services. The case is interesting since the services in question were deemed similar only on the basis that they were complementary in nature. Similarity can be found solely on this basis (following the Kurt Hesse case), but it is relatively rare.

The High Court held that the UK IP Office Hearing Officer was entitled to take judicial notice of her own experience when determining how the services in question were sold. She was entitled to find that "air transportation services" are similar to a lowish degree to "hotel services; resort lodging services; reservations services for hotel accommodations" because, "Whilst dissimilar in nature, purpose and method of use, these services are commonly sold through the same channels of trade as air transport. The people who fly to a destination will also be those using accommodation services at the destination. The services are not in competition but package holidays, which feature flights, transfers and hotels, are readily available from a wide range of operators, resulting in complementarity."

Given the identity of the marks, the acquired distinctiveness of the prior DELTA registrations for air transportation services at large and the lowish degree of similarity between the services, there was a likelihood of confusion between the marks. The use of the DELTA mark for hotel, restaurant and various retail services would also take unfair advantage of the reputation of the prior DELTA registrations even in the absence of a subjective intent by the owner of the later mark to exploit that reputation. The DELTA registration was therefore partially invalidated.

In Health and Happiness v EUIPO, the EU General Court has issued a reminder that parties must substantiate all grounds they rely on in invalidity proceedings.

The applicant for invalidity had provided detailed submissions that the contested registration was invalid on three grounds: that it was misleading, illegally exploited the name of a state and had been applied for in bad faith. No submissions had been filed in support of its claim that the registration was invalid for lack of distinctiveness.

The General Court reflected that, although there is a degree of overlap between the absolute grounds for refusal, each ground must be considered independently and cannot be conflated with the others. Since the applicant for invalidity put forward no substantive arguments that the mark lacked distinctive character, the Cancellation Division and Board of Appeal had been wrong to evaluate the mark on distinctiveness. They should only have considered the grounds substantiated.

The position should be contrasted with that where a trade mark application is opposed where the Board of Appeal is entitled to decide on "all issues which, in the light of the facts, evidence and arguments provided by the parties and the relief sought, are necessary to ensure a correct application of [the EU Trade Mark Regulation] and in respect of which it has all the information required in order to be able to take a decision, even if no element of law related to those issues has been relied on by the parties before it." (C-702/19P). Indeed, the EU IP Office is entitled to assess (and raise objections based on) inherent registrability of its own volition at any time up until a mark is registered.

In this series

Yoga Alliance: a reduction in protection for descriptive trade marks?

25 April 2023

SOUNDGRAM not confusingly similar to INSTAGRAM or GRAM, confirms High Court

25 April 2023

by Simon Jupp

Related Insights

UK to maintain current exhaustion of rights regime

A fireside chat with Guy Parker of the ASA and Jason Freeman of the CMA