- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- A round up of key de…

- On this page

12 December 2023

Brands Update - December 2023 – 7 of 8 Insights

In case you missed it: designs! A round up of key design law related developments in 2023

- In-depth analysis

Following on from our round up of key trade mark law related developments this year (Part 1 and Part 2), here is more of the same but – this time – covering design law.

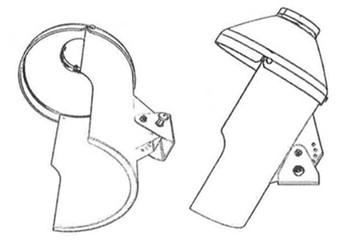

When is a design excluded from protection because it fulfils a technical function: Papierfabriek Doetinchem?

In Papierfabriek Doetinchem, the ECJ confirmed that the exclusion under Article 8(1) of the Design Regulation applies where the need to fulfil a technical function is the only factor determining the choice of the designer of a feature of appearance of a product (applying the DOCERAM decision) - in other words, where considerations of another nature, in particular visual considerations, have not played a role in the choice of the feature in question.

This makes sense given that Article 8(1) is intended to prevent technological innovation from being hampered, providing that design protection does not subsist in features of the appearance of a product which are dictated solely by their technical function.

The existence of alternative designs achieving the same technical function is not in itself sufficient to enable the registration of the design, otherwise a single economic operator would be able to monopolise certain technical features by registering alternative designs incorporating those technical solutions. In this respect, design law is comparable to trade mark law which also prohibits the registration of shapes or other characteristics of goods necessary to obtain a technical result – and the fact that the same technical result can be achieved otherwise is irrelevant.

The packing-paper dispenser design the subject of the Papierfabriek Doetinchem ruling

The court concluded that the assessment of whether a feature of appearance of a product is dictated solely by its technical function must be made having regard to all the objective circumstances relevant to each case including the choice of features of appearance, the existence of alternative designs which fulfil the same technical function, and the fact that the proprietor of the design in question also holds design rights for numerous alternative designs.

The ECJ also stated that the mere possibility of a multicolour appearance (which may suggest that the design feature may not have been dictated solely by its technical function) is subjective in nature and it cannot be taken into account if that multicolour appearance does not appear in the registration of the design at issue. This is because the competent authorities and the public must know with clarity and precision the nature of the constituent elements of a design in order to ensure legal certainty. Therefore, visual considerations (such as a design consisting of two components allowing for the multicolour appearance of a product) may be considered if they appear in the design registration in the context of the technical function assessment, but they are not decisive.

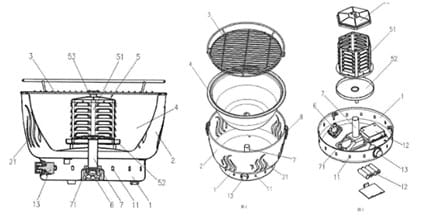

Can a transfer agreement with retroactive effect get round the grace period requirements: Activa - Grillkuche?

There is a one-year grace period to register a design after it has been made available to the public. This potentially allows the design to be tested in the market before the cost of registration is incurred. If the design is not applied for within this one-year time limit, it will not be considered new. To rely on the grace period, the design must (largely) have been disclosed by the designer or its successor in title.

In Activa - Grillkuche v EUIPO, an application for a Registered Community Design had been filed by a different entity to that which had earlier created and disclosed the design. Subsequently, the parties put in place a transfer document which had retroactive effect (to a date earlier than when the design had been disclosed). The question was whether the disclosure was by the designer or a successor in title such that it did not destroy the novelty of the subsequent design registration.

The General Court confirmed that the Design Regulation does not prohibit contracts which are signed after the date of filing of a design application and that retroactively transfer intellectual property rights provided that the retroactive clause is not contrary to EU rules and does not involve any risk of fraud. Parties have freedom to conclude contracts transferring property and this cannot be limited. Of particular importance in this case was the fact that the entity that disclosed the design and the entity that applied for the registered design had a business relationship – the former being the supplier of the latter - long before the design was disclosed or applied for. This was not therefore a case of fraud.

The design disclosed in the Activa case

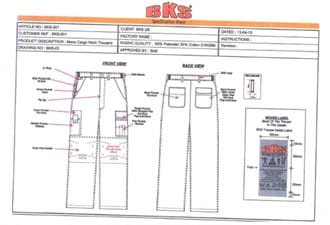

When is UK unregistered design right new: KF Global v Lead Wear?

In KF Global Brands v Lead Wear, the High Court of England and Wales (IPEC) has ruled on subsistence of design right (a separate species of unregistered design in the UK) when changes are made to an existing design. The Court said that "…where a new design is produced by making changes to an existing design, it is for the Court to decide whether the changes are relatively minor. If so, then no new design right will arise in the new design as a whole but merely in those parts which have changed. It might still be open to the creator of the minor design changes to rely on the design right in the existing design, but only if he or she happens to own that design right too."

The case concerned alleged infringement of design right in cargo trousers. The design right relied on in the infringement action itself reproduced an earlier third-party design with the exception of a pen pocket. The infringement claim failed because the claimant did not rely on any design right in the pen pocket only. It could not rely on design right in the whole product (the cargo trousers) since this was not original (being copied from the third-party product). The case illustrates the importance of claiming design right in the correct features of a product.

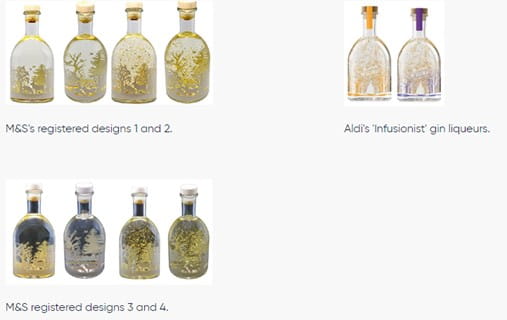

Striking similarities: Aldi infringes Marks & Spencer's UK registered designs

The High Court (IPEC) has ruled that Aldi's festive gin-based liqueur, The Infusionist, infringed Marks & Spencer's four earlier UK registered designs for gin globes. M&S's designs consisted of a botanical shaped bottle, stopper, a winter scene (mainly consisting of tree silhouettes) on the entirety of the straight sides of the bottle, a snow effect (on two of the designs) and an integrated LED light in the base of the bottle (on two of the designs).

In holding infringement, the court paid particular attention to the fact that the designer had considerable design freedom, only one other prior design (forming the design corpus) had a botanic shape and snow effect (but that prior design did not contain the other elements of M&S's designs) and that the cumulative similarities between the designs would be striking to the informed user. The court also confirmed that, where a registered design has a priority date, infringement is assessed as at that date.

It is worth noting that M&S filed applications to register the designs in the UK after it had launched its product (within the 12-month grace period) and after Aldi had launched its infringing product. The case shows the value of registered design protection especially for seasonal or short-lived products – and that it is sometimes possible to register designs (or other IP rights) after an infringement has come to light to bolster the case. More on this case here.

How does technical function impact infringement: Chiaro Technology v Mayborn?

In Chiaro Technology Ltd v Mayborn (UK) Ltd, the High Court has ruled that three registered designs relating to a wearable breast pump had not been infringed because the defendant's product created a different overall impression on the informed user considering the limited design freedom of the designer (due to the functional requirements of the product at issue).

The court noted that technical function should be determined objectively without considering the subjective view of the designer. The contents of patents (including those of the design owner and third parties) are objective evidence of the functional features of a design but they are not conclusive proof of technical functionality (Nintendo v Compatinet and Benmore Ventures v 2W).

The High Court also clarified that the correct starting point for considering design freedom is the design itself not the design corpus and that it doesn’t matter that there might be other ways of achieving the same technical result. If a feature of a design is functional, it cannot be the basis of an infringement claim and cannot be considered when assessing the overall impression on the informed user.

This case illustrates how difficult it is to protect new and innovative designs where a number of features of the product each have a technical function.

What constitutes "normal use" for the visibility requirement: first ECJ decision in Monz v Buchel?

In Monz v Büchel, the ECJ has issued a first preliminary ruling on the interpretation of the requirements of "visibility" and "normal use" for component parts of complex products in Articles 3(3) and 3(4) of the Design Directive.

These Articles state that, a design applied to or incorporated in a product which constitutes a component part of a complex product shall only be considered to be new and to have individual character if the component part, once it has been incorporated into the complex product, remains visible during normal use of the latter. "Normal use" means use by the end user, excluding maintenance, servicing or repair work. The provision aims to ensure that designs that are not visible (eg because they are internal to a product) are not capable of protection.

The design of the underside of a bicycle seat, the subject of the Monz case

The ECJ clarified that a component part of a complex product enjoys protection under design law if it remains visible in the context of normal use and that the intended use by the manufacturer is not the only factor. The visibility requirement must be assessed from the perspective of the end user as well as an outside observer. In this context, use for its intended purpose is to be interpreted broadly and includes all actions undertaken in the course of the principal use of the product, as well as those actions which the end user is normally required to undertake in the course of such use, for example storage or transport of the product, but with the exception of maintenance, servicing and repair, which are specifically excluded in the Directive.

The ECJ's decision will be welcome by many design owners, especially from the industrial sector. Its broad interpretation of the term "normal use" expands the possibilities for protection of complex products under design law. For more, see our article here.

In a ruling issued the following day, the Board of Appeal confirmed the validity of a design for heated socks applying the broad interpretation of "normal use" developed in Monz. The Board of Appeal noted that normal use of a stocking includes plugging and unplugging the battery, in which case all the elements of the contested design remained visible.

Is a consumable product, such as an electrode, a component part of a complex product: B&Bartoni v EUIPO?

In B&Bartoni v EUIPO, the Board of Appeal addressed the question of whether a consumable product (in this case, an electrode) constitutes a component part of a complex product (in this case, a welding torch) and therefore subject to the visibility requirement set out in Article 4(2) of the Design Regulation.

The welding torch in question

The Board of Appeal noted that the Design Regulation does not define the concept of a 'component part of a complex product' and that, according to the ECJ, a component part covers "multiple components, intended to be assembled into a complex industrial or handicraft item, which can be replaced permitting disassembly and re-assembly of such an item, without which the complex product could not be subject to normal use" (Acacia and D’Amato, C 397/16 and C 435/16).

However, the Board of Appeal clarified that the phrase "without which the complex product could not be subject to normal use" cannot be interpreted as requiring that, in the case where the complex product cannot fulfil the function for which it is intended without another product, that other product must be regarded in all cases as a component part of the complex product. This is a question of fact which must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, according to a set of relevant factors.

In the present case, the Board of Appeal decided that an electrode is not a component part of complex product considering:

- the absence of a firm and durable connection with the torch

- the short lifespan of the electrode

- the fact that the electrode is intended to be replaced regularly and in a straightforward manner without requiring the disassembly and re-assembly of the torch

- the interchangeability of the electrode (the Board of Appeal noted that a product which can be replaced by another identical product is less likely to be linked in a durable and tailored manner to a complex product)

-

the fact that the torch is regarded as complete without the electrode (the Board of Appeal noted that the torch could be offered on the market without the electrode and that electrodes are commonly advertised and sold separately from torches).

This decision clarifies that products of a consumable nature can be eligible for design protection as a separate product and therefore not subject to the visibility requirement.

What are the impacts of the changes to designs law in the EU?

There are proposals to modernise EU legislation on designs at EU-wide level (covering RCDs and UCDs) and national member state level (covering the national species of design).

The proposals would particularly make the system more accessible and fit for purpose in the digital age. Key changes include the expansion of the definition of a design (to include the movement, transition or any other sort of animation of the features of the appearance of a product) and the definition of a product (to include such things as digital products and the spatial arrangement of interior environments).

If adopted, the proposals will see UK and EU law on designs diverge. The UK has also indicated that it will conduct a further consultation on the UK design regime next year. For more on the EU proposals, see our article here.

What is the WIPO Conference on Design Law Treaty?

Various sessions of the WIPO Standing Committee on the Law of Trademarks, Industrial Designs and Geographical Indications have taken place in October 2023 aimed at agreeing a Design Law Treaty (DLT). Saudi Arabia will host a Diplomatic Conference in November 2024 to conclude and adopt the DLT. The DLT aims to streamline the formalities associated with applications for the protection of industrial designs (but not the substantive law). Various papers on the Treaty can be found here including the draft Treaty itself.

In this series

Prior rights that cease to exist during an action: Advocate General issues first Brexit-related Opinion

24 November 2023

Changes to the EU regulations on geographical indications for wines, spirit drinks and agricultural products

12 December 2023

New EU GI Regulation for Craft and Industrial Products: importance for brand owners not just in the EU

12 December 2023

Descriptiveness of earlier mark mitigates against infringement: VETSURE v PETSURE (HC)

12 December 2023

Likelihood of confusion found between a Cyrillic and Latin character mark

12 December 2023

In case you missed it: designs! A round up of key design law related developments in 2023

12 December 2023

Related Insights

The case all marketing teams should read - Dryrobe v Caesr Group

When laudatory marks are given broad protection: Sexy Fish

by Christian Durr and Louise Popple

easyGroup v Premier Inn: Court rejects family of marks monopoly and clarifies section 10(3) protection

by Louise Popple and Moira Sy