The High Court has dismissed easyGroup's trade mark infringement claims against Premier Inn's "Rest Easy" campaign. What does this judgment tell us about the strength of descriptive marks, family of marks, surveys and reputation-based claims?

What has happened?

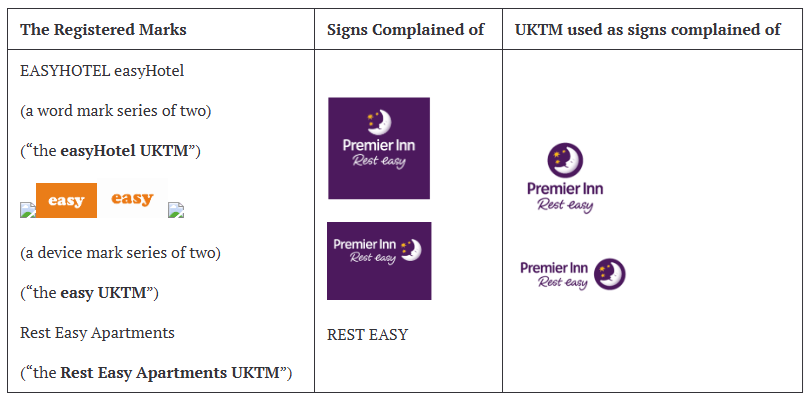

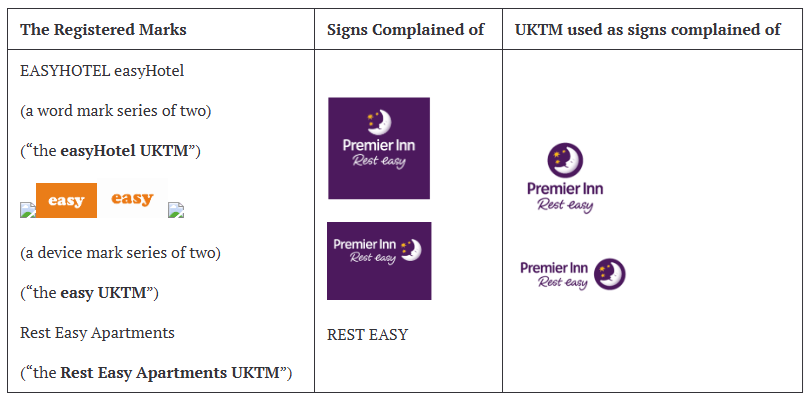

- easyGroup brought claims for both a likelihood of confusion and unfair advantage/detriment to reputation, alleging Premier Inn's "Rest Easy" campaign infringed its easyHotel, easy, and Rest Easy Apartments trade marks.

- The likelihood of confusion claim – which was based on easyGroup's Rest Easy Apartments registration only – failed either because the "Rest Easy" signs had only been used in text by Premier Inn (no trade mark use) or formed part of the wider Premier Inn logo. There was also a lack of evidence of actual confusion.

- The reputation-based claim failed at the "consumer link" stage, with the court finding no evidence of a link, despite easyGroup searching over 17 million emails and 120 terabytes of data. In any event, no evidence of a change in the economic behaviour of consumers was offered, with easyHotel's revenues actually increasing substantially during the period of Premier Inn's campaign.

- Furthermore, the court found no unfair advantage (this was "fair competition") and no detriment to distinctiveness (with others in hospitality having used the words "rest easy" before and since).

- The judgment shows that it is difficult to stop others using descriptive words as part of normal text (not as a brand) and as part of a wider mark with other distinctive elements. Here, this not only negated confusion but also a link.

- There is also useful guidance on surveys, wrong way round confusion and family of marks. The judge held that easyGroup could not rely on any family of marks arguments, having expressly disavowed such arguments at an earlier hearing. This could be subject to an appeal, which would be interesting as easyGroup questioned whether family of marks arguments could apply to reputation-based as well as likelihood of confusion claims.

Want to know more?

The trade mark claims

easyGroup sued Premier Inn for trade mark infringement over Premier Inn's "Rest easy" branding. The claims comprised: (1) infringement under section 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA) based on easyGroup's "REST EASY APARTMENTS" word mark; and (2) infringement under section 10(3) of the TMA based on easyGroup's "EASYHOTEL" mark and the stylised "easy" figurative mark. Premier Inn's allegedly infringing use consisted of "Rest easy" as an endline in a lock-up with the "PREMIER INN" name and moon device, as well as occasional textual "rest easy" in marketing materials.

Section 10(2): likelihood of confusion

Section 10(2) of the TMA provides that a person infringes a registered trade mark if they use in the course of trade a sign which is similar to the trade mark and is used in relation to goods or services identical with or similar to those for which the trade mark is registered, where there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public.

The court found low similarity between Premier Inn's "Rest easy" sign and easyGroup's "REST EASY APARTMENTS" mark. "Rest easy" is a common idiom, and the dominant element of Premier Inn's mark was the PREMIER INN name and moon device rather than the "Rest easy" endline. The court found a medium similarity between letting/rental of apartments and hotel services.

The court found no likelihood of confusion, given the low mark/sign similarity, the low distinctiveness of the shared words, and the dominance of the PREMIER INN name and moon device in Premier Inn's sign. The court noted that almost four years' parallel use had occurred with no evidence of actual confusion, which weighed against a finding of infringement. The court held that the Medion principles (which can allow infringement where an earlier mark retains an "independent distinctive role" in a composite sign containing a well-known company name) did not assist easyGroup on these facts.

The court also found that there was no wrong way round confusion (people seeing Rest Easy apartments would not think it was related to Premier Inn).

Lastly, there was no likelihood of confusion where the words "Rest Easy" were used in marketing copy. There is a technical problem with the ruling here as, where a mark is not being used as a trade mark, the courts normally hold that there is no use "in relation to" the relevant goods/services as opposed to no use "in the course of trade" (the latter being what the court held here). There could be an appeal here since the parties agreed that there was use "in relation" to relevant goods/services by Premier Inn.

Section 10(3): unfair advantage and detriment

Section 10(3) of the TMA provides protection for marks with a reputation against use which, without due cause, takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or repute of the trade mark. Unlike section 10(2), there is no requirement for a likelihood of confusion, but there must be a "link" in the mind of the average consumer between the sign and the mark.

The court found that the "EASYHOTEL" mark had reputation (was well known) and moderate enhanced distinctiveness for hotel/temporary accommodation services only. However, the stylised "easy" device had no reputation or enhanced distinctiveness in the registered Class 43 hotel services. While easyGroup's consumer surveys complied with the Whitford guidelines, they did not show reputation or enhanced distinctiveness for the stylised "easy" device. Notably, the court excluded easyGroup's coding analysis from consideration as it was conducted by the claimant's solicitor instead of an independent expert.

The court found very low visual and aural similarity between the marks and signs, and no conceptual similarity. On a global assessment, the court found no link between Premier Inn's use and easyGroup's marks, noting the absence of any evidence of consumers making a link despite approximately 6 million items of customer feedback being searched.

In any event, a successful claim of unfair advantage and detriment to distinctiveness requires evidence of a change in the economic behaviour of consumers or serious risk of such change. easyHotel's revenues actually increased substantially during the period of Premier Inn's campaign.

Furthermore, the widespread use of "rest easy" by other businesses in the hotel sector supported the finding that Premier Inn's use would not dilute the distinctive character of easyGroup's marks, particularly as "rest easy" as a common phrase is not equivalent to "easy" as a brand identifier.

Likewise, there was no evidence of unfair advantage. The court found no proof that Premier Inn benefited from a transfer of image or piggybacking on easyGroup's reputation. Specifically, easyGroup's assertions that Premier Inn was able to attract customers it would not otherwise have reached, and that the "Rest Easy" rebrand had been "enormously successful", were unsupported by evidence. Premier Inn's internal emails showed no plan to exploit easyGroup's reputation and they simply did not consider that there was any risk of doing so. After undertaking a multifactorial assessment, the court found that Premier Inn's rebrand launch was conducted by way of fair competition and consequently, unfair advantage could not be established by easyGroup.

The family of marks argument

At an earlier hearing, easyGroup had said that it did not intend to rely on a family of marks argument in this case – and this was recorded in an order.

It sought to change its mind at trial, including by bringing in family of marks arguments via the back door (eg by arguing that the easyHOTEL registration receives a reputation boost from the other easy brands).

There was some dispute at trial about exactly what the words in the Order meant (and whether easyGroup was foregoing the family of marks argument only in relation to its likelihood of confusion claim or in relation to the reputation-based claims as well). There was also dispute about whether family of marks-type arguments are even relevant to reputation-based claims.

However, the judge ruled that easyGroup was not allowed to rely on any family of marks arguments at all. That will no doubt be subject to an appeal.

What does this mean for brand owners?

- Context matters. Where a potentially similar sign appears alongside strong house branding (here, "PREMIER INN" and the moon device), that context can be decisive in avoiding confusion.

- Descriptive words and phrases receive generally narrower protection. The courts will not normally find normal textual use of descriptive words as trade mark use.

- The "link" threshold is significant. For section 10(3) claims based on marks with a reputation, establishing that consumers will make a mental "link" between the sign and the mark is a crucial threshold requirement. Mere similarity is not enough; the consumer must actually call the earlier mark to mind. This can be difficult to establish where the word or sign has a meaning in ordinary language and appears in a different context.

- Survey evidence must be robust. Consumer surveys must comply with established guidelines (such as the Whitford guidelines) and must be conducted independently. Coding by a party's own solicitor may be excluded from consideration, particularly if not properly disclosed to the court or court permission is not obtained in advance.

- Proving a change in the economic behaviour of consumers (or a serious likelihood of such a change) is essential – merely asserting that there would be such a change is insufficient.

In this series: