- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- Context of use is ke…

13 July 2023

Brands Update - July 2023 – 1 of 5 Insights

Context of use is key when deciding trade mark infringement: Umbro's claim fails

- Briefing

The recent High Court (England and Wales) decision in Iconix v Dream Pairs is a useful reminder that the context in which a mark is used is a core factor in whether or not there is infringement.

What has happened?

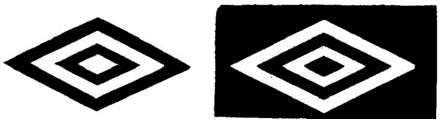

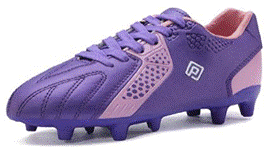

- The case relates to the use on football boots and trainers by Dream Pairs of a logo allegedly similar to the well-known Umbro logo mark of Iconix (both depicted below). Iconix sued for trade mark infringement.

- The Defendant's products were sold on Amazon under the name Dream Pairs.

- The High Court reiterated that, when deciding whether or not there is trade mark infringement, the overall context of the use by the Defendant should be taken into account.

- On that basis, combined with the Court finding a low level of similarity between the logos, Umbro's infringement claim was unsuccessful.

-

It is important to remember the distinction between the test for trade mark infringement and how oppositions against trade mark applications are determined. In trade mark infringement, the context of use is taken into account whereas in oppositions it is not (although notional and fair use is assumed). So it is entirely possible that an opposition could succeed but – with context of use taken into account - an infringement claim fail.

Want to know more?

The background

Iconix (Umbro) owns trade mark registrations for its well-known logo:

Dream Pairs sold football boots and trainers via Amazon, using this logo:

The logo appeared alone in some places on its products, but the Dream Pairs name was present on some products and always referenced in the Amazon listings:

|

|

The High Court's ruling

The High Court characterised the Defendant's logo as "a broken square with a P-shape in the middle" and decided that it had only a low level of similarity with the "flat, elongated diamonds" Umbro logo. When combined with the context of use – including the Dream Pairs name and no reference to Umbro – there was no likelihood of confusion and the infringement claim under section 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA) therefore failed.

The Court also found that the low level of similarity between the logos meant that no "link" with Umbro would be made by consumers when seeing the Dream Pairs logo, even if the Dream Pairs name was not visible in all contexts. So the reputation/unfair advantage claim under section 10(3) TMA also failed.

Further considerations

The Court reaffirmed the important distinction between the assessment of trade mark infringement – where the context of actual use is taken into account – and the test in an opposition against a trade mark application, where logically context of use is not relevant. A trade mark being applied for comprises just the trade mark and therefore covers all possible types of actual use for the goods/services specified by the application (although notional and fair use is assumed).

Authority for this distinction goes back to the ruling of the European Court of Justice in the O2 Holdings v Hutchison case on a reference from the UK Court of Appeal. It was reaffirmed in the UK Court of Appeal's judgement in Specsavers v Asda [2012] EWCA Civ 24. In that case, Asda made use of the signs "spec saver" and "spec savings" as a play on words in straplines in its promotional materials. The Court of Appeal placed weight on the overall context of Asda's usage, in particular that this made clear it related to Asda and not to Specsavers. This led to a finding that there was no likelihood of confusion.

However, Specsavers' claim did succeed on the basis of reputation/unfair advantage. The Court decided that, whilst the context of use meant there was no likelihood of confusion, consumers would still make a mental link with Specsavers when seeing the Asda advertisements.

The reason why Umbro's reputation/unfair advantage claim failed was primarily because the Court decided that the Dream Pairs logo was not sufficiently similar to Umbro's logo for consumers even to make a link. The outcome would almost certainly have been different (and arguably should have been anyway) if the Dream Pairs logo had been more closely similar to the Umbro one.

What does this mean for you?

- When dealing with a claim based on a mark with a reputation, it is important to bear in mind that the context of use may not be sufficient to avoid a link being made by consumers and therefore infringement being found. For a claimant, it will usually therefore be a good idea to include a reputation/unfair advantage claim when available.

- Importantly and by contrast, a defendant facing an infringement action, where the earlier mark does not have a reputation, can potentially have a defence if the way it uses a sign – including for example in combination with its house mark or in the clear overall context of that house mark - is sufficient to mean that consumers are in reality unlikely to be confused.

In this series

Context of use is key when deciding trade mark infringement: Umbro's claim fails

13 July 2023

UKIPO considers brand extension and family of marks arguments: JACK AND VICTOR not similar to JACK / JACK DANIELS for whisky

13 July 2023