- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- In for a penny – in…

- On this page

21 March 2023

In for a penny – in for a digital pound?

- Briefing

CBDC Taskforce publishes plans for a digital pound

On 7 February 2023, the joint Bank-HM Treasury CBDC Taskforce (the Taskforce) published a consultation paper on a potential retail UK central bank digital currency (CBDC). This 'digital pound' would be a new form of sterling, similar to a digital banknote, issued by the Bank of England for everyday use by households and businesses. We consider the case for a CBDC, the proposed model and key milestones.

Introduction

At the outset, the Taskforce makes it clear that while it is likely a digital pound will be needed in the future, it is too early to commit to building the infrastructure, being a major piece of national infrastructure likely to require several years to complete. The digital pound will need the backing of deep public trust as to safety, accessibility and privacy, built through an open national conversation about the future of money alongside detailed technical consideration by experts. This consultation is aimed at starting this conversation and beginning to build that foundation of public trust.

The consultation is complemented by a detailed Technology Working Paper from the Bank of England, exploring the many technology challenges involved in a digital pound. It explores technology design considerations and sets out further technical detail on the model for the digital pound set out in the consultation (although in the consultation, the Bank makes it clear this is just one and not the only possible approach and provides a summary of alternative models).

Back to Basics

Before diving into the detail of the platform model for the digital pound, its objectives and likely timescales, a couple of key conceptual distinctions need to be made:

- Private Money v Public Money. Presently, individuals and businesses in the UK use two main forms of money– private money, issued by commercial banks, and public money, issued by the Bank of England. ‘Private money’ is typically a claim on a private commercial bank in the form of bank deposits (underpinned by the regulation and supervision of commercial banks). ‘Public money’ or ‘central bank money’ is issued by the Bank of England to the public, presently, as physical cash only (financially risk-free since there is no credit, market or liquidity risk). Importantly, the Taskforce makes it clear that the digital pound is not aimed at replacing cash which continues to be an essential means of payment for many.

- Retail CBDC v Wholesale CBDC. The retail digital pound subject to this consultation needs to be distinguished from ‘wholesale CBDC’, used to settle high-value payments between financial firms; the Bank already provides central bank money in electronic form for wholesale settlement through its Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) service. The Bank is improving this service through its RTGS Renewal Programme and, following consultation with industry, the Bank is developing a Roadmap for RTGS Beyond 2024.

New Digital Pound

The proposed model for the digital pound is based on three core themes (aimed at meeting the objectives we explore in the next section):

- the platform model built on public-private partnership

- data protection and privacy

- user experience.

Public-private platform model

The digital pound infrastructure would be publicly provided and open to use by the private sector, to promote innovative and efficient payment (and other services) by the private sector.

- By a platform model, the Taskforce means that the Bank would build and operate a 'core ledger' on which it would record the digital pounds it issues. This ledger would be highly secure, fast and resilient technology platform, operational 24/7 and providing the minimum necessary functionality for the digital pound.

- A payment made in digital pounds between two users would be processed and settled by a transfer on the Bank’s core ledger. The exchange of digital pounds into other forms of money, for example bank deposits, would involve links to other payment systems. The Bank would receive payment messages instructing transfers on the core ledger in anonymised form and would not know the identity of the payer and payee. The exact technology behind the ledger is still being discussed and covered in further detail in the Technology Working Paper.

- The platform would be accessible through an application programming interface to Payment Interface Providers (PIPs) and External Service Interface Providers (ESIPs) (both regulated private firms). PIPs and ESIPs would build on the platform by developing and offering innovative digital pound services and deal with all user-facing interactions.

- ESIPs. They would provide non-payment related value-add services. Examples of such services include business analytics, budgeting tools and fraud monitoring.

- PIPs. They would provide interactions relating to payments and be responsible for initiating payments (although the transfer of holding and settlement would, not surprisingly, occur at the Bank level). A PIP authorised to operate in the digital pound system would automatically be able to undertake the activities of an ESIP.

- Digital 'Pass-Through' Wallets. The digital pound would be provided to users through digital pass-through wallets. They are ‘pass-through’ because user’s holdings of digital pounds are recorded on the Bank’s core ledger, and the wallet simply passes instructions from the user to that core ledger. Therefore, the private sector would never be in possession of users’ digital pound funds. They would be responsible, however, for recording the identity of users and carrying out any necessary know-your-customer and anti-money laundering checks. Wallets would be flexible but need to have minimum functionality to allow users to access digital pounds, to make payments, to view balances and transaction history, and mobility (i.e. ability to switch providers and close wallets).

This model does indeed have great potential of promoting innovation and competition. Having the core infrastructure developed and maintained at the public level, would allow authorities greater control over barriers to entry to the market and has the potential to significantly reduce such barriers (a significant advantage to existing payment systems in which considerable entry barriers face indirect participants and which regulators have less control over).

The Taskforce has also expressed willingness to work on proportionate regulatory requirements for PIPs and ESIPs. Of course, innovation and competition should always be balanced against security and customer protection. The Taskforce recognises that there is a single point of failure risk and there are many conversations yet to be had with experts and important decisions to be made in relation this. Success of the system also depends on there being sufficient incentives for the private sector to participate and so the Taskforce is seeking views on various revenue models.

Data protection and privacy

The Taskforce notes that rigorous standards of privacy and data are fundamental to building trust and confidence in the digital pound. It notes that the public continues to be concerned about issues relating to the storage and use of their personal data, especially now the UK economy has become more digital. Therefore, the digital pound would have at least the same level of privacy as a bank account and would also allow users to make choices about data use.

The Taskforce has summarised the privacy objectives for the digital pound in the following diagram. There is a clear intention to strike the right balance between protecting and empowering users on the one hand, and the realities of the digital payments world and the ability to use data in innovation on the other.

[Source: Bank of England and HM Treasury, 'The digital pound: a new form of money for households and businesses?', Consultation Paper, February 2023.]

User Experience

The digital pound would be used for everyday payments by households and businesses both in-person and online. In the consultation, the Taskforce focuses on individual user experience. In relation to the business use case, the Taskforce recognises further research is needed (the key issues being how many digital pounds they should be allowed to hold (given the wide variety of their size) and which types of corporates should be allowed access (eg excluding financial firms to ensure the purpose of the digital pound remains largely retail)).

For individuals, at least, the digital pound would support two essential types of payment:

- Person-to-business (P2B), both ‘in-store’ and ‘online’.

- Person-to-person (P2P), such as sending money to a friend.

The key elements of the user experience of the digital pound are as follows:

- Who would use the digital pound? All UK residents and non-UK residents (provided certain requirements as to the regulatory regime of their home jurisdiction are met) when visiting the UK (eg tourists), and when outside the UK for payments with either a UK or non-UK resident.

- How would users spend and receive digital pounds? Payments in digital pounds may involve a variety of devices including, but not limited to, smart devices, cards, websites and apps, point-of-sale devices (including ones already in existence). All these would be developed by the private sector, with the Bank setting minimum standards. Currently there is no intention for the digital pound to be remunerated, it would not pay (nor charge) an interest rate.

- What types of payments would the digital pound be used for? Initially, it would be in-store, online and person-to-person but this may broaden out in future. The Bank is willing to allow any payments so long as they are lawful, observe any restrictions and comply with regulatory obligations.

- How many digital pounds can a user hold? During the introductory stage, it is proposed that there would be an individual limit of between £10,000 and £20,000. This is to manage any risks to financial and monetary stability (while supporting wide usability of the digital pound). The Taskforce welcomes views on a lower limit, such as £5,000, but states this could make the digital pound less useful.

- How would the digital pound interact with other forms of money? Moving between digital pounds and other types of money must be fast and easy. However, the extent to which existing and prospective infrastructures can support interoperability for the digital pound is still very much subject to in-depth technology research. The Technology Working Paper discusses the options for enabling certain interoperability.

All this dedication to flexibility and innovation gives great hope that the digital pound may revolutionise the future of money and solve longstanding problems such as limited and inconvenient means of P2P payments, the ever-higher fees for card payments and the very costly cross-border payments. However, whether providers would indeed be able to leverage existing infrastructure and whether it would be possible to integrate the digital pound with existing means of payment is a big remaining question mark for the technology experts which would decide the digital pound's future.

Objectives

The Taskforce has two primary motivations for the digital pound:

- To sustain access to UK central bank money. The digital pound would have a role as an anchor for confidence and safety in the monetary system, and to underpin monetary and financial stability and sovereignty. Uniformity and trust in the safety of money could be threatened by a combination of lower cash use and the emergence new forms of private digital money (which could end up being used in fragmented way). This could result in sterling no longer being used for a significant portion of UK transactions, compromising monetary sovereignty (ie the UK authorities’ ability to achieve price stability through monetary policy). The digital pound could support the uniformity of money by replicating the role of cash in a digital economy.

- To promote innovation, choice, and efficiency in domestic payments. Innovation boosts the UK economy and supports growth, inclusivity and efficiency. But innovation can come with risks of concentration. Based on the public-private platform model, the digital pound could support innovation with more limited concentration and without crowding out other forms of payment.

Other motivations include enhancing financial inclusion, payments resilience and improving cross-border payments.

Timescales and Next Steps

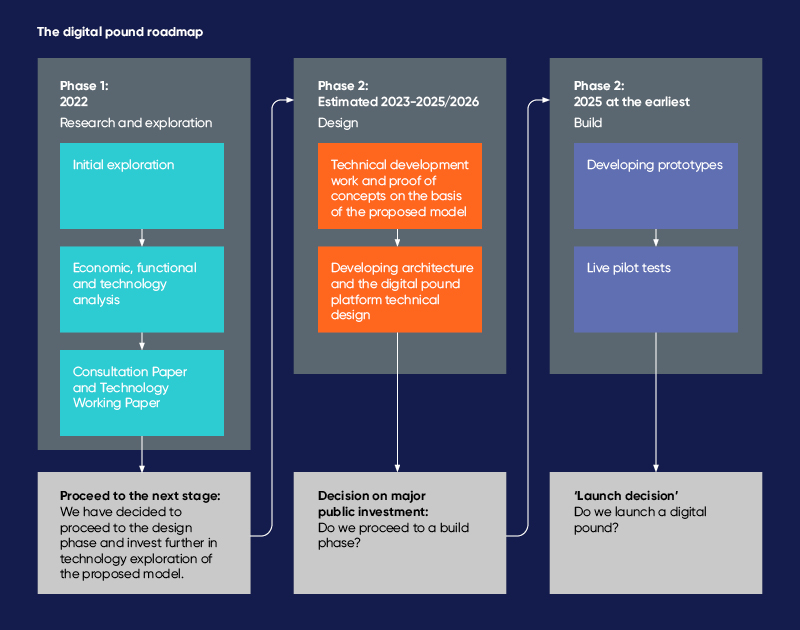

- Phase 1 'research and exploration'. This consultation and the Technology Working Paper are the conclusion of Phase 1.

- Phase 2 'design'. The Taskforce will now move to Phase 2, to develop further the technology and policy behind the model set out above. It will evaluate comprehensively if a digital pound is technologically feasible, determine the optimal design and technology architecture, and support business model innovation, working closely with the private sector. After the design phase, and following further consultation, there will be a decision on whether to build a digital pound.

- Phase 3 'build'. Phase 3 would involve developing a prototype digital pound technology in a simulated environment, before moving to live pilot tests. A digital pound would only be launched if, among other things, it meets the Taskforce's exacting standards for security, resilience, and performance.

[Source: Bank of England and HM Treasury, 'The digital pound: a new form of money for households and businesses?', Consultation Paper, February 2023.]

This article has been published in www.compliancemonitor.com and www.i-law.com.

Related Insights

Stablecoins: no longer the new kid on the block

by multiple authors

Financial Services Matters - February 2026

by multiple authors

Financial Services Matters - January 2026

by multiple authors