- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- Getty Images v Stabi…

2025年7月9日

Radar - July 2025 – 4 / 4 观点

Getty Images v Stability AI: where are we after the trial - copyright?

- In-depth analysis

Where are we after trial, why were some claims dropped and what can we learn from the case?

The copyright claims

Getty originally advanced three claims:

- Primary infringement by copying during the training and development stage.

- Primary infringement by authorising copying by end users or communication to the public at the output stage.

- Secondary infringement by importation, possession and/or distribution etc of an article which is an infringing copy.

The two primary infringement claims were dropped (along with the two database right infringement claims) towards the end of the trial, leaving only the secondary infringement claim.

The training and development claim - dropped

Getty alleged that there was infringement by copying under section 17 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA) as a result of the training and development by Stability of its Stable Diffusion model.

The precise nature of Getty's claim – and the way it was defended - is important here. Getty alleged that datasets containing infringing copies of its works were downloaded and stored by Stability in the UK during the training and development of Stability's model. Stability defended the allegation on the basis that the datasets were never downloaded or stored in the UK and that it was not responsible for some of the earlier versions of the model. There was no separate issue in dispute about whether there was copying in the sense required by section 17 of the CDPA or whether the temporary copies exception applies (both unlikely to have succeeded on the facts here).

To understand how this claim came to be dropped, it's useful to consider some of the background.

Stability tried to strike out this claim in mid 2023 on the basis that no relevant activities occurred in the UK. That application was refused. While the judge found "strong support for a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, no training or development" took place in the UK, she also held that there was evidence potentially pointing away from this, inconsistencies, gaps and reasonable grounds to believe that disclosure might add to or alter the evidence. This was partly based on the fact that some Stability employees and contractors were based in the UK and/or employed by the Stability UK company. There's a clear indication in the judgment that Getty's pleadings on the training and development claim would need to be amended when the evidence came in from Stability.

Those amendments never happened (or perhaps never fully happened). Instead, Getty applied to court to introduce a Statement of Case on training and development (SOCTD) just over two months before trial to address new lines of enquiry opened up by Stability's disclosure and gaps in Stability's evidence. It was largely too late. When giving judgment on the application, the judge was clear that Getty should have applied to amend its pleadings as a priority following disclosure to particularise the facts it now sought to address. Had it done so, it might have flushed out further evidence and disclosure from Stability. Getty's original pleadings were "inchoate" and "inferential" because the evidence it needed was with Stability. That's why it advanced its case "pending the provision of disclosure and/or evidence". It could not maintain that position and use it as a "get out of jail free card" to "run whatever case it likes on the evidence at trial".

Getty's claim, therefore, largely hung on whether the witnesses that Stability had put forward stood up under cross-examination at trial. They largely did. Those called to give evidence were fairly adamant that all work was undertaken on non-UK cloud-based servers and that it would not have been necessary to download any training datasets onto UK computers or servers (which would not, in any event, have been powerful enough to undertake any training or development).

In view of this, it's easy to see why Getty felt that it had no option but to drop the claim. Given what the judge had said previously, it was always going to be difficult for Getty to ask the judge to draw adverse inferences against Stability due to gaps in Stability's evidence and the absence of key witnesses. Even though there might have been some merit to Getty's arguments that the evidence was missing, it was fairly clear from the judge's ruling on the SOCTD that she wasn't going to draw adverse inferences that she considered unparticularised and speculative.

Whether the judge would have drawn any adverse inferences even if Getty had amended its pleadings is difficult to say. It looks as though there were new lines of enquiry arising from Stability's disclosure that merited being pursued, including new datasets on which Stability's model was possibly trained and additional individuals based in the UK. However, it doesn't look like there was a "smoking gun" linking activities to the UK.

Getty's training and development claim was not an easy one. Stability's model was trained in stages using different datasets/subsets and by different groups (some possibly academic). It was an incredibly factually complex scenario, not helped by Stability's lack of record-keeping and limited witness evidence. The timetable was incredibly tight, with disclosure in November 2024, only seven months before trial (and only in unredacted form in January 2025). It's easy to see how it ended with the claim being dropped – and it's quite possible that no infringing activities did, in fact, occur in the UK.

What can we learn from this?

- If AI developers needed any more confirmation of what to do to avoid infringement at the training and development stage in the UK, this case is it. Nothing should be downloaded and stored in the UK, this fact should be made clear to employees and contractors through training and written policies and records should be kept to confirm compliance.

- Those who undertake training or development (or hold datasets) in the UK should not be buoyed by the fact that the training and development claim was dropped. Had Getty been able to show that relevant activities occurred in the UK, this would have been a very different case.

- If the judge finds secondary infringement by importing or possessing etc (see below), it might not matter where training and development occurs (except possibly for damages).

- This case says nothing about whether there was copying in the sense required by section 17 of the CDPA or whether the temporary copies exception applies. It was defended on other grounds.

- Claimants have always needed to think carefully about what jurisdiction(s) to bring their claims bearing in mind the facts and availability of copyright defences. This case shows that those decisions can be difficult, especially where information is unclear.

- Disclosure requests need to be extremely clear and well thought through. Requests to search computers, for example, should expressly extend to personal computers used for work purposes.

- It is imperative that claimants consider whether any aspects of their pleadings need to be amended as a case progresses, particularly following disclosure. The judge called Getty's failure to do so a "fundamental procedural error". Claimants should not delay in making amendments and in seeking further disclosure or information, even where timetables are tight.

The output claim - dropped

Getty alleged that there is infringement at the output stage, when Stability's model produces synthetic images, by communication to the public under section 20 (or authorising acts of copying by end users under section 16(2)) of the CDPA. The claims related to text-to-image outputs, image-to-image outputs and text + image-to-image outputs.

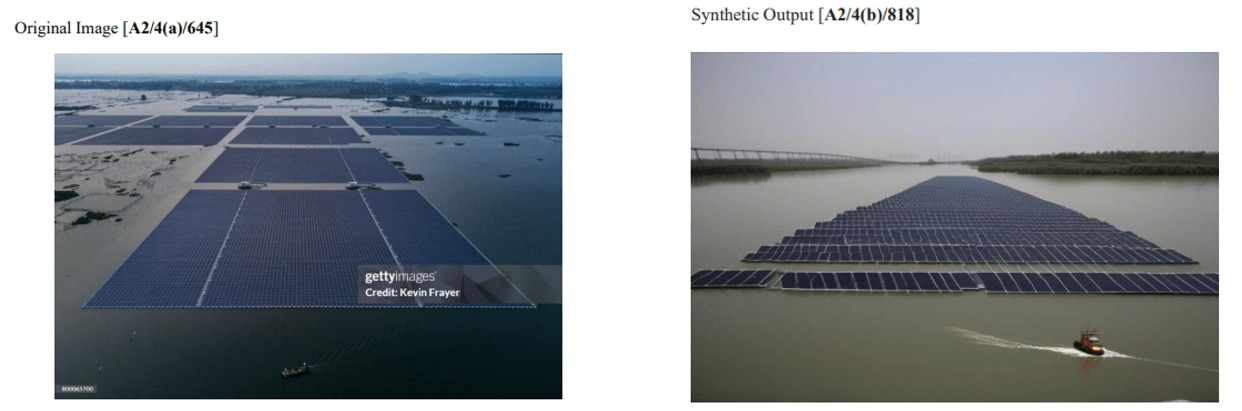

At an earlier hearing, Getty had agreed to particularise this claim further by providing examples of copyright works alleged to have been infringed, although it was agreed that they need not be representative. It supplied around seventeen. Ominously, by the time the trial started, that number had been reduced to thirteen (with Stability citing chain of title issues as the reason and Getty being silent on the point). Here are a couple of the thirteen that Getty relied on.

SOCI Work A2: Floating solar panels in China

SOCI Work A5: Jurgen Klopp

Stability argued no infringement on numerous grounds, but its main arguments were that it had not copied a substantial part of any of Getty's thirteen works, that Getty lacked title to some of the works, and that the alleged infringements were produced by wilful contrivance by Getty.

Getty says that it dropped this claim because Stability has now successfully been able to block all use of the prompts complained of (for the text-to-image output claims) for the current cloud-based versions of its model, negating any need for an injunction. While we don't know exactly what has been agreed, if only the specific prompts used to generate the thirteen alleged infringements have been blocked and only in this narrow way, this does not seem like much of a victory for Getty.

Part of the difficulty for Getty is the way latent diffusion models work. The process of generating synthetic images involves starting with adding random noise to an image and backwards engineering an image from the "noisy" version of the image. It doesn’t produce the same image each time, even with the same prompt. While there can sometimes be memorisation (the production of images nearly identical to training images), the experts disagreed on the circumstances required and how likely memorisation was to occur. Getty's expert was of the view that the circumstances under which Stability's model was produced would have made memorisation more likely (as evidenced by the presence of Getty watermarks). However, the lack of a clear memorised output to rely on in the copyright claim did not help Getty.

The experts did agree that the two images above were both derivatives (derived from multiple similar images) and that – for the Klopp image - the Getty assets contributed. However, it's easy to see why Getty was concerned that this might not be enough to show the copying of a substantial part. This is particularly so as many of the images relied on by Getty (including the Klopp one) are arguably of low originality – a matter conceded by some of the Getty photographer witnesses. They would therefore be given a relatively narrow scope of protection. Establishing that a "substantial part" of a protected element has been taken is not easy in these circumstances.

Even if Getty had been able to get over the line on substantial part, the chain of title and wilful contrivance issues remained. By the end of the trial, title to nine out of the thirteen works alleged to be infringed remained in dispute, with the issues being so complex that over 70 pages of Getty's skeleton were devoted to title in general.

Almost as much space was spent on the wilful contrivance issue. This is Stability's argument that infringing outputs are largely only a theoretical risk and that Getty designed its prompts and experiments with the sole purpose of "forcing" infringements. The prompts used by Getty were not completely outlandish. They consisted of prompts matching the captions used to describe the images in Getty's library, reworded versions of those prompts and other invented prompts (such as those including the words "news photo" or "vector art"). Whether a Stability user would have used such prompts is another matter. Neither party was able to put forward a realistic estimate of the probability of an infringing output in the real world.

It is disappointing that we won't get a ruling on this, particularly the implications if Stability's argument was accepted that the probability of an infringing output in the real world is somewhere between small and zero. Does that mean that there is no infringement, is it to be taken into account when deciding remedies or is it completely irrelevant? There is no precedent for this. The judge might have to address this question as part of the trade mark infringement claim and it is hoped that, whatever she decides, can be transferred to future copyright cases.

After such a long piece of litigation, it is also disappointing that we won't get what would have been a very valuable ruling on other aspects of the output claim, particularly on the questions of derivation from the original work, reproduction of a substantial part, wilful contrivance, communication to the public when a single user receives the output initially, authorising user infringement and the scope of any injunction that would have been granted had infringement been found. Those thinking of pursuing output infringement claims will be closely studying the arguments in this case.

What can we learn from this?

- It's going to take a different type of case to show reproduction of a work in a training dataset at the output stage, where it is easier to connect the output work to a specific input work and where there's an easier argument on "ordinary" uses infringing (and less argument of wilful contrivance).

- Any ruling on wilful contrivance in the trade mark context might help understand how the issue will be approached in the copyright context.

- AI developers will no doubt be considering how they can block certain prompts and types of output to minimise output infringement risks. They should also be considering proactive steps to filter out NSFW and other illegal and unwanted content.

- Making sure that authorship and chain of title are secure is key. It is an issue that arises in most copyright infringement claims and can easily undo the claim. It is always worth reviewing standard practices for obtaining title and considering how they can be improved, as Getty may well be doing now.

- More generally, there is a lesson here on managing IP rights in general. Stability alleged that Getty had extinguished any database right that existed in its image library by transferring title in that library to its US arm. Issues like this need to be considered before IP rights are dealt with.

- Although it probably won't get them 'off the hook' for infringement, AI developers should ensure that they have clear T&Cs and that they prohibit users from doing anything that infringes IP rights and do what they can to minimise/discourage infringing uses.

The importation and possession etc claim - live

The remaining claim – and arguably the most significant and interesting - is of secondary infringement. Getty's allegation is that Stability has imported an article (namely, the model weights) which is – and which Stability knows or has reason to believe is - an infringing copy of Getty's copyright works contrary to section 22 of the CDPA. (Its claim as regards section 23 fell with the training and development claim, although Stability doesn't seem to have got that message.)

The parties agree that the model weights are supplied to users when they download Stability's model but that the model weights do not contain the images used to train the model themselves. No model weights are supplied to users for the cloud-based version of Stability's model. It is hardly surprising then that Getty's main arguments on this relate to the downloadable versions of Stability's model although it did plead secondary infringement for both the downloadable and cloud-based versions. It is also worth bearing in mind that Stability does not argue that the safe harbour defence applies for the downloadable versions of its model.

The claim largely hinges on two questions of law, neither of which has previously been decided: whether an article can be an infringing copy if it no longer retains a copy of the copyright works; and whether an article can be something intangible such as model weights.

- Can an article be an "infringing copy" if it does not contain a copy of the copyright works? Getty points to section 27 of the CDPA, which says that an article is an infringing copy if its making would have constituted an infringement had it occurred in the UK. It does not particularise this allegation further. Stability does not challenge Getty's argument per se (probably because it accepts that at least some Getty copyright works were used to train certain models). Rather, it counters that an article cannot be an infringing copy if it no longer contains a copy of the allegedly infringing works. Both parties point to case law to support their positions but – as the judge noted in her decision to refuse summary judgment on this issue in 2023 – none of the authorities go to the point. This issue would probably not arise if we were talking about a physical article such as a memory stick – if any infringing copies were deleted from such an article, it would be difficult to argue that the article is still an infringing copy. The situation is more subtle here. We are talking about an article that Getty says retains some 'residue' of the copyright works but not the works themselves.

- Can an article be something intangible such as model weights? Getty argues that the word article includes tangible and intangible articles (such as model weights). It finds support for its position in various sections of the CDPA, including section 17, which says that copying includes "reproducing the work in any material form" including "storing the work in any medium by electronic means" and "the making of copies which are transient or are incidental to some other use of the work". It relies on the "always speaking" principle of statutory interpretation, which requires an Act of Parliament to be interpreted so as to cover new technological developments which the legislators might not have foreseen if they conform to the policy of the Act in question. Stability points to other sections of the CDPA that possibly cut against this interpretation and relies on the natural language of "importation" and "possession", which it says implies something tangible. It also relies on a statement in Hansard (records of parliamentary debates) when the CDPA was being enacted in which Lord Beaverbrook (the minister responsible) rejected a suggestion to extend secondary liability for copyright infringement to intangible broadcasts and cable transmissions. It might therefore boil down to whether the judge considers the legislation ambiguous such that she is permitted to refer to Hansard and – if so – whether she considers Lord Beaverbrook's comment to rule out secondary liability for copyright infringement for all intangible articles or just broadcasts and cable transmissions. In any case, Stability's argument that intangible infringements were intended to be dealt with as part of the primary, not the secondary, infringement provisions (see eg the original form of section 20, which covered primary liability for intangible infringements in the form of broadcasts and cable transmission before communication to the public was introduced), remains available even if Hansard is not admissible and is one of Stability's strongest arguments (albeit one that does not get much air time).

Assuming Getty is able to get over these hurdles (possible), it would have to show that Stability's model is an "infringing copy" as a matter of fact, the requisite knowledge/reason to believe and that the acts of importation occurred (or are threatened).

What can we learn from this?

- The wider implications of a finding of secondary liability could be huge, impacting the provision of many AI models (and other content) to UK users. This will no doubt be weighing on the judge, particularly given the UK government's consultation and ongoing dialogues about the extra-territorial reach of copyright law and AI policy. If the judge considers the legislation ambiguous and decides that it is a matter for parliament to consider, there will be a finding of no infringement. However, the judge might be swayed by Getty's argument based on a judgment by Lord Bingham in the Designers Guild case, that “no one else may for a season reap what the copyright owner has sown”. If that is top of mind, there could be the opposite finding.

- A finding of liability would be mitigated if it is limited to downloadable versions of the model only. This would leave Stability (and others) free to supply the web-based versions of its model to UK users, which Stability says are hosted on servers located outside of the UK. It should also mean 'business as usual' for cloud-based SaaS providers hosted from outside of the UK. If there is a ruling to this effect, it would be a victory for Getty but not the full one it would want.

- It's highly likely that the secondary infringement ruling will be appealed, potentially to the Supreme Court – but the government might legislate on the issue before it gets there.

- Those who provide content and services to UK consumers from overseas will be watching this aspect of the ruling carefully. It could have significant consequences for infringement.

What next?

The judge has said that a decision is unlikely before the summer recess but she will aim to deliver it in the next court term. Given how meticulous she is, expect a long and well-thought-through ruling.

本系列内容

The final GPAI Code of Practice: Key insights, unresolved questions, and parallel regulatory tracks

2025年7月11日

作者 作者

European Commission guidelines on protection of minors under the Digital Services Act

2025年7月29日

Related Insights

The case all marketing teams should read - Dryrobe v Caesr Group

When laudatory marks are given broad protection: Sexy Fish

作者 Christian Durr 以及 Louise Popple

easyGroup v Premier Inn: Court rejects family of marks monopoly and clarifies section 10(3) protection

作者 Louise Popple 以及 Moira Sy