24 November 2015

The challenge of true IP harmonisation - Part 2

In the second part of a two part extract from the Globe Law & Business title "Intellectual Property in the Life Sciences" (second edition), Paul England discusses the extent to which intellectual property rights are harmonising to meet the challenges of a globalised life sciences industry.

Does the commercial globalisation of the life sciences business and the international reach of the legal framework mean that intellectual property is now largely harmonised from one country to another? The answer is no. The reasons for this are complex, but they include differences of implementation, or lack of implementation, of international instruments into national laws, different legal traditions with competing influences and, not least, different approaches in national courts. This is perhaps most obvious in the European context. Take, for example, an issue fundamental to patent protection – the approach taken to the scope of protection of patent claims. For the countries subject to the European Patent Convention (EPC), Article 69 of the EPC and its attendant Protocol on interpretation describe how the scope of protection of a claim is to be determined:

Article 1 - General Principles

Article 69 should not be interpreted as meaning that the extent of the protection conferred by a European patent is to be understood as that defined by the strict, literal meaning of the wording used in the claims, the description and drawings being employed only for the purpose of resolving an ambiguity found in the claims. Nor should it be taken to mean that the claims serve only as a guideline and that the actual protection conferred may extend to what, from a consideration of the description and drawings by a person skilled in the art, the patent proprietor has contemplated. On the contrary, it is to be interpreted as defining a position between these extremes which combines a fair protection for the patent proprietor with a reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties.

Article 2 - Equivalents

For the purpose of determining the extent of protection conferred by a European patent, due account shall be taken of any element which is equivalent to an element specified in the claims.

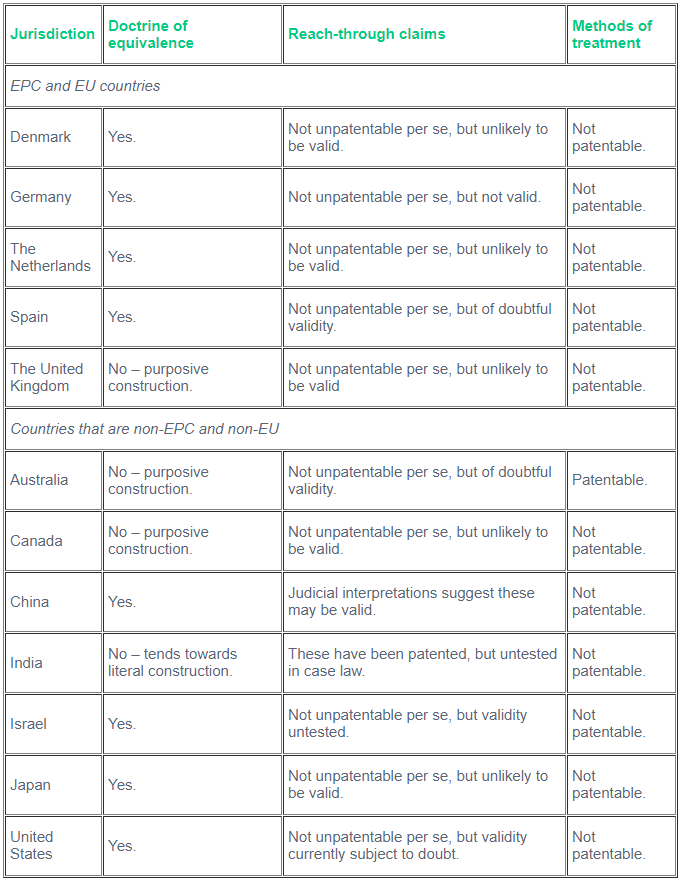

However, reconciling the Protocol with the existing approaches of the courts of European countries is difficult. The most obvious manifestation of this can be seen in their attitude towards the so-called 'doctrine of equivalence' – construing a claim to include embodiments of the invention that are not literally included in the claim but are nonetheless equivalent to literal embodiments by function, means, result or other technical characteristics. As the table below shows, within Europe the UK jurisdictions stand out for not applying a doctrine of equivalence, despite Article 2 of the Protocol. Nonetheless, it has been held by the House of Lords (now replaced by the UK Supreme Court) that the purposive approach adopted by the UK courts is in keeping with this provision.1 Whilst the German courts and Dutch courts will apply the doctrine of equivalence in appropriate cases, the ways they do so are different too, even though they also are at pains to follow the Protocol. There are other important differences – in Germany there is no doctrine of file wrapper estoppel, but in the Netherlands amendments made to a claim in prosecution may be referred to when construing the granted claim of a Dutch patent.

However, the European courts in which patents are most often litigated appear to be increasingly conscious that this situation needs to change. The statement of Jacob LJ in Grimme Maschinenfabrik GmbH v Scott2 illustrates this:

"Broadly, we think the principle in our courts – and indeed that in the courts of other member states – should be to try to follow the reasoning of an important decision in another country. Only if the court of one state is convinced that the reasoning of a court in another member state is erroneous should it depart from a point that has been authoritatively decided there."

Indeed, shifts in national approaches are still occurring in this important area. In particular, the Bundesgerichtshof in Occlusion Device3 overturned the very broad scope of claim protection applied by the lower courts in favour of applying a narrower, claim-centred approach, consciously bringing it closer to its European neighbours. The result of the case – non-infringement – is the same as the cases on equivalent European patents heard in the English and Hague Court of Appeals. More recently, the pemetrexed cases in the English and German courts have provided a gauge of how close these jurisdictions are on determining scope of claims.

The backdrop of any discussion about European patent matters is the fact that the European Commission is close to establishing a European patent with unitary effect (“Unitary Patent”) that will have a unitary, protective effect over most European Member States. Under associated plans, disputes concerning this Unitary Patent, as well as European patents, are to be litigated in the Unified Patents Court. As well as the costs savings that this system is intended to have, the system of mixing judges from different jurisdictions together in the panels hearing cases is intended to create convergence of European approaches to patent law into a single body of UPC law. How successful the new court and the new patent will be and, indeed, quite when they will be established, remain unknown.

What about further afield than Europe? Returning to the doctrine of equivalence, a slightly different picture emerges outside Europe, which says much about the complexities of international patent law and the barriers to true harmonisation. The table shows that the United Kingdom is not actually alone in disavowing the doctrine of equivalence as a means to patent claim construction; neither do Australia, Canada or India adopt it. This exposes one of the competing traditions that lies beneath much intellectual property law: Commonwealth countries have close and recent connections with English common law and many of the concepts and approaches once shared have remained. English cases in these countries may still be influential and vice versa. By contrast, the United States, also a common-law country but one that has had more than two centuries of travelling in its own direction, has its own, rival influence in the world. This influence is particularly noticeable in China. Both the advent of TRIPS and the drive to create innovation-based life sciences sectors in China – benefiting from huge domestic markets, as well export opportunities – is bringing about rapid development in the area of intellectual property law and its associated regulation there. It is a breathtaking transformation. As Judge Jiang Zhipei, former Justice of the IP Tribunal, Supreme People’s Court of China, has explained,4 China has spent three decades on the road to completing the modernisation of its IP regulatory system, whilst many Western countries achieved the same over two or three hundred years. The Chinese courts are not working in isolation. China is following and studying the decisions and procedures of other countries, particularly the United States, on matters such as claim construction, to see how they can improve the judicial interpretation of Chinese law

But the complexities of international intellectual property law resist any easy analysis. Column 3 of the table shows that there are unexpected approaches to be found in the emerging economies. Of the countries in the table, it is only India and China where it currently seems most likely that reach-through claims could survive a validity challenge. Then again, look at the fourth and final column. Here, the EPC countries are unified in their exclusion of method-of-treatment claims, by virtue of Article 53 EPC:

European patents shall not be granted in respect of:

… (c) methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy or diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body; …

Likewise, they are excluded from patentability in India, Japan, China, Israel and Canada. But in Australia and the United States there is no such exclusion.

Table: The approach to the doctrine of equivalence, reach-through claims and methods of treatment in sample EPC signatory countries and elsewhere

This article is an extract from the forthcoming Globe Law & Business title "Intellectual Property in the Life Sciences", published in November 2015.

If you have any questions on this article or would like to propose a subject to be addressed by Synapse please contact us.

1 Kirin-Amgen Inc and Others v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd and Others [2004] UKHL 46.

2 2010] EWCA Civ 1110.

3May 10 2011 – X ZR 16/09 – Occlusion Device.

4Speaking on April 4 2011.

5Global Intellectual Property Index, The 4th Report, 2013.

Related Insights

UK medicines – Is the Northern Ireland Protocol now unsustainable?

English patent torpedoes and the UPC

Has there been a shift in how the European courts approach preliminary injunctions?

by Dr Paul England and Christoph de Coster, LL.M. (UC Davis)