- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- Court of Appeal conf…

2026年1月22日

Brands Update - January 2026 – 5 / 7 观点

Court of Appeal confirms registrability criteria for position marks

- Briefing

What has happened?

- The Court of Appeal in the case of Thom Browne v Adidas has adopted a definition for "position marks" which are to be understood as the combination of a visual element and its position on the goods, with their distinctive character deriving at least in part from their positioning.

- The appeal concerned the validity of six UK position mark registrations which the High Court had deemed invalid on the basis that they did not consist of a single sign and lacked clarity and precision.

- The Court of Appeal has upheld that ruling, finding that the High Court judge had not erred in law or principle.

- The Court of Appeal confirmed that, while the appearance of a position mark may vary within permissible limits, it cannot constitute a multiplicity of signs. The public must still perceive the same sign and not be confused as to the origin of the goods or services.

- It also confirmed that, as the distinctive character of position marks derives at least in part from their positioning, if that position is not clearly specified, then the registration requirements of clarity and precision may not be met.

- The decision confirms how difficult it can be to describe a position mark where the aim is to protect the mark on numerous locations (positions) on the goods. It follows similar (largely failed) attempts by Cadbury to register the colour purple as applied to the packaging of its goods (more here). Where there is only one position for a mark, it will be much easier to describe (see, for example, this position mark on a bicycle sprocket). The difficulty arises where the placement of a mark might vary on the goods and the applicant tries to cover a number of possible placements in one trade mark application.

Want to know more?

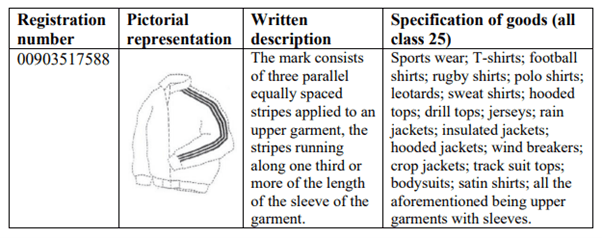

The appellant appealed the High Court's findings that six of its position UK trade mark registrations were invalid. An example of one such registration is below.

A trade mark (including a position mark) can be registered if it satisfies three independent and cumulative conditions. It must be (1) a sign, (2) capable of being represented in the register (previously, capable of graphic representation) in a clear and precise way, and (3) capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another.

Applying conditions (1) and (2) at first instance, the High Court found that the subject matter of each position mark was not a single sign, nor was it represented clearly and precisely. The latter was due to the descriptions of the marks using insufficiently precise language and extending more broadly than the accompanying pictorial representations. The court found the public would perceive the marks as intended to cover a wide variety of different forms, making it unclear what the marks consisted of.

The Court of Appeal upheld the ruling. It emphasised that the mere existence of possible variations within a trade mark does not automatically render it invalid on ground (1). The key consideration is whether, in the light of those variations, the public would still perceive the same mark and not be confused as to the origin of the goods or services. It is therefore not strictly necessary for every variation to be depicted in separate images or registrations – what matters is whether all reasonable variants would be viewed, from the consumer’s perspective, as essentially "the same mark". However, in this particular case, the Court considered that the combination of image and description resulted in a registration encompassing a multiplicity of signs. For the same reasons there was also lack of clarity and precision under ground (2). The Court held that this breadth created uncertainty as to scope of each of the marks and that the registrations were invalid.

By contrast, the EU IP Office's (EUIPO) Cancellation Division found the same registrations valid under its own standards. While EUIPO decisions are influential, they do not bind the Courts of England and Wales, and this case demonstrates a clear divergence between UK and EU practice.

What does this mean for you?

- This is the first English court authority on position marks, demonstrating how these non-traditional trade marks carry a greater risk of invalidity, though they may be perceived differently in various jurisdictions.

- When applying for position marks in the UK, brand owners should ensure that any trade mark description and pictorial representations are precise and consistent. It is important to avoid ambiguous or overly broad descriptions that could create uncertainty about what is protected, and each application should narrowly and accurately define the mark’s appearance and exact placement on the goods.

- While filing multiple applications to protect variations of a mark (rather than relying on a single, wide-ranging registration) is not strictly necessary, it can mitigate the risk of invalidity, so should be considered by brand owners if variations are noticeable.