- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- Lidl v Tesco

2023年5月31日

Brands Update - May 2023 – 2 / 9 观点

Lidl v Tesco: key learnings

- In-depth analysis

The case illustrates the importance of keeping records of why a trade mark application was filed and how logo and figurative marks were created. It also illustrates the potential scope of passing off and copyright infringement claims.

What has happened?

- The High Court has issued its decision in the Lidl v Tesco case concerning Lidl's objection to Tesco's Clubcard Prices logo.

-

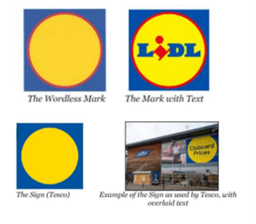

The case concerned Tesco's use of a yellow circle in a blue square for its loyalty scheme, Clubcard Prices, which Lidl claimed infringed its trade marks, and constituted passing off and copyright infringement. The Lidl logo also consists of a yellow circle (but with a red outline) in a blue square. It is registered as several trade marks in the UK, including with the word Lidl (called the mark with text), and without the word Lidl (called the wordless mark).

- Interestingly, Lidl did not bring a likelihood of confusion-based trade mark infringement claim, but a reputation-based claim. The court accepted the extensive evidence of the reputation of Lidl's logos. It held that the Tesco and Lidl logos were similar, despite some containing different word elements. Any differences in word elements did not extinguish the strong similarity conveyed by the logos' backgrounds. The court concluded that the use of the Tesco logos took unfair advantage of the reputation of the Lidl marks, in particular the value proposition conveyed by those marks. It was also detrimental to the distinctive character of the Lidl marks.

- There was a small victory for Tesco in that it was able to invalidate some of Lidl's trade mark registrations for the wordless mark on the basis that they were applied for in bad faith (as a defensive weapon to use against others and to circumvent the proof of use requirements for registrations more than 5 years old). However, this did not alter the overall outcome of the case.

- Importantly, at an earlier hearing, the Court of Appeal had held that the objective circumstances raised by Tesco were sufficient to create a rebuttable presumption of lack of good faith such that the burden of proving no bad faith now passed to Lidl. Lidl was not able to explain the rationale for the initial or repeat filings and so its registrations were invalidated (except for a 2021 registration, which survived).

- Lidl's claim in passing off was passing off as to equivalence rather than trade origin. Lidl was able to successfully argue that a substantial number of customers would be misled to believe that the Tesco Clubcard Price was the same/lower than the Lidl price for the equivalent goods. That mistaken belief would deceive consumers and cause damage to Lidl because price sensitive shoppers would switch from Lidl to Tesco.

- Lidl also won on copyright infringement. Given the degree of similarity between the logos and the fact that Tesco had access to the Lidl logos, the burden of proving lack of copying passed to Tesco. It was unable to discharge that burden.

What does this mean for brand owners?

- The case illustrates that brand owners must be careful not to stray too close to their competitors' marks even if those marks consist of seemingly commonplace and banal elements. Simply adding different words to a mark might not be sufficient to avoid a finding of trade mark infringement.

- It also illustrates the importance of creating and maintaining records to justify why particular trade mark applications were filed (to rebut potential bad faith arguments). This is particularly so for repeat filings and where a mark might not be used in the form in which it was registered (including where it might be used as a component part of another mark) or where there are other unusual circumstances.

- Brand owners should not assume that they will be deemed to have filed an application in good faith just because they subsequently use the mark in question. Bad faith and use are different issues. Where there might not have been an intention to use a particular mark at the time of filing, but use is later commenced, a new filing might be merited.

- Protecting component parts of complex marks can sometimes be merited. Careful consideration should be given before any filing particularly as to whether and how easy it will be to prove use and any bad faith angles.

-

Passing off is not always as to trade origin. It can also be as to equivalence or false endorsement. It is a potentially wide tort that can sometimes go beyond a traditional trade mark infringement claim. This risk should be factored into the trade mark clearance process.

-

Copyright can subsist in what some might view as banal logos. Brand owners should keep detailed records as to the genesis of any logo or figurative element of a brand to corroborate lack of copying. The risk of a copyright infringement claim should also be factored into the trade mark clearance process.

Want to know more?

Trade mark infringement

Lidl sued Tesco for trade mark infringement relying on a reputation-based claim under section 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

Lidl was able to provide substantial evidence that its marks had a significant reputation for supermarket services in the UK.

The court considered Tesco's logos to be similar to both Lidl's wordless mark and its mark with text. This was despite the fact that Tesco's logos were nearly always used with words. The court held that visual similarity was key, the logos all being primarily viewed visually by supermarket shoppers. Any differences in word elements did not extinguish the strong similarity conveyed by the logos' backgrounds. Supermarket shoppers would be likely to focus on those backgrounds (the word elements largely comprising of promotional statements or the words Tesco or Lidl). This conclusion was reached by virtue of external reports and customer feedback put forward by Lidl.

Although confusion was not an element to be proved, there was clear evidence of both origin and price match confusion/association, together with evidence that Tesco's employees also appreciated the potential for confusion, which fortified the findings of similarity.

Lidl submitted strong evidence (eg surveys and witness statements of consumers) as to the link in consumers' minds between the Tesco logos and the Lidl marks.

The court concluded that the use of the Tesco logos takes unfair advantage of the fame of the Lidl logos, as Tesco benefits from the value proposition conveyed by the Lidl logos. Such use was also detrimental to the distinctive character of Lidl's logos as it would dilute the latter's uniqueness (as evidenced by the fact that Lidl was compelled to undertake corrective advertising).

Accordingly, trade mark infringement was established.

Trade mark invalidity

By way of counterclaim, Tesco sought a declaration of invalidity against a number of registrations for Lidl's wordless mark, on the grounds of non-use, non-distinctiveness and/or bad faith.

Non-use and distinctiveness

The Court dismissed the non-use arguments, finding that the wordless mark had been put to genuine used by virtue of the mark with text, as consumers would (at least in the last few years) consider both iterations as originating from Lidl (applying the case of Specsavers v Asda).

The Court also dismissed the non-distinctiveness argument as the evidence showed that the specific combination of simple geometric shapes and primary contrasting colours was memorable and distinctive of trade origin for Lidl's logo.

Bad faith

Tesco counterclaimed that Lidl had no genuine intention to use its wordless mark registrations and that they had therefore been applied for in bad faith, on the basis that:

- Lidl had applied for the wordless marks as a defensive weapon, solely to use against others and to widen its monopoly

- Lidl had filed successive applications for the wordless marks to circumvent the rules on proving use (so-called ever-greening).

Importantly, at an earlier hearing, the Court of Appeal had held that the objective circumstances raised by Tesco were sufficient to create a rebuttable presumption of lack of good faith by Lidl such that it was now for Lidl to provide a plausible explanation of its objectives and commercial logic. Those circumstances were the combination of:

- Repeat filings

- The assertion that Lidl had had no intention, at the time of filing the original wordless application, of using the wordless mark

- The fact that that Lidl had never used the wordless mark.

Lidl was not able to explain the rationale for the repeat filings (except for a 2021 registration which therefore survived). The court therefore had no option but to find bad faith and invalidate the registrations. Key findings of the court were as follows:

- A finding of actual use is not sufficient to protect against a finding of bad faith. The fact that a registered mark is later found to have been used as a component part of another mark does not (without more) evidence the existence of the necessary intention to use at the time of filing.

- Lidl's evidence and arguments did not address why the wordless mark was originally filed. Likewise, there was no evidence that Lidl knew or thought that it was using the wordless mark by using the mark with text. That the original wordless mark was filed as a legal weapon was therefore a permissible inference from the evidence.

- Lidl was unable to explain why later wordless applications duplicated (at least, in part) the goods and services of earlier applications.

- A 2021 registration for the wordless mark survived since there was evidence that, by that point, Lidl genuinely believed that use of the mark with text also constituted use of the wordless mark as well as evidence that the wordless mark enjoyed its own reputation. The fact that there was a 13-year gap in filings by the time the 2021 registration had been filed also suggested that Lidl did not have an ever-greening strategy by that point.

The case is consistent with previous rulings on bad faith including the EU General Court's Monopoly ruling (see our article here). What is interesting is that the burden of proof shifted to Lidl to prove good faith. That was fatal to Lidl and might well be to others who have no records to justify why a particular trade mark application was filed.

This raises the question of how much evidence the other side must produce for the burden to shift in this way. Clearly, this case was somewhat unusual in that Lidl's wordless logo is a component part of another mark (just as the Specsavers logo and the Levi's red tab). Proving an intention to use it (or proving that Lidl thought that use of the word with text also constituted use of the wordless logo) was always going to be difficult, absent any records.

Whether the burden of proof would have shifted to Lidl without that factor (ie just on the basis of lack of use and repeat filings or even just one of these) is unclear. Either way, trade mark owners are advised to create and maintain detailed records as to why particular trade mark applications have been filed to help fend off any bad faith allegations. These will be particularly important should the burden of proving no bad faith shift to them.

The case also illustrates that brand owners should not assume that they will be deemed to have filed an application in good faith just because they have subsequently used the mark in question. Where there was no genuine intention to use a particular mark initially (or there is no evidence as to that intention), then refiling for a mark might be appropriate if there is now a desire to put that mark into use. The subsequent application should be deemed to have been filed in good faith even if the earlier one(s) was/were not.

Passing off

Lidl's claim of passing off was as to equivalence (price and value) rather than trade origin. The Court relied on its findings and evaluation of evidence from the trade mark claim. Specifically, goodwill was found because a UK public would recognise Lidl's marks, evincing its reputation as a discount supermarket.

Lidl was able to successfully argue that a substantial number of customers would be misled to believe that the Tesco Clubcard Price was the same/lower than the Lidl price for the equivalent goods. That mistaken belief would deceive consumers and cause damage to Lidl because price sensitive shoppers would switch from Lidl to Tesco.

The decision shows the potential scope of a passing off claim.

Copyright infringement

Lidl's mark with text was considered an artistic work, capable of copyright protection under sections 1 and 4 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. It was treated as a graphic work, which is protected "irrespective of artistic quality" and the Court emphasised that the scope of protection is a question of fact, not degree.

Lidl's mark was also found to be original, as the act of bringing together the Lidl text with the yellow circle and the blue background was deemed to involve the exercise of intellectual creation, involving the expression of free choice. Indeed, Tesco's own evidence as to the various combinations of apparently basic shapes and colours considered by its own designers demonstrated the creative freedoms in relation to the sign.

Given the degree of similarity between the signs and the fact that Tesco had access to the Lidl logos, the burden of proof on showing there was no copying passed to Tesco. Unable to discharge that burden, having also failed to obtain evidence from the external design agency which helped create the Clubcard Prices logo, Tesco was found to have copied a substantial part of Lidl’s mark with text, and thus infringed Lidl’s copyright.

This is an important reminder that copyright can subsist in seemingly banal logos and of the importance of having detailed records as to the genesis of any logo or figurative element of a trade mark to corroborate lack of copying.

This article was co-authored by Kachenka Pribanova.

本系列内容

Related Insights

The case all marketing teams should read - Dryrobe v Caesr Group

When laudatory marks are given broad protection: Sexy Fish

作者 Christian Durr 以及 Louise Popple

easyGroup v Premier Inn: Court rejects family of marks monopoly and clarifies section 10(3) protection

作者 Louise Popple 以及 Moira Sy