- Accueil

- Actualités et public…

- Publications

- Renewed push for ons…

- Sur cette page

8 février 2024

Renewed push for onshore wind power in the UK

The Climate Change Committee (CCC), the statutory body advising the UK government on matters including greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, has just published a key document on COP28 key outcomes and next steps for the UK.

Published on 30 January 2024, this report documents that:

- COP28 assessed that globally, actions are far behind what is urgently needed to reduce carbon emissions

- recognition at COP28 that there is growing momentum in renewables and other low-carbon technology deployment. The call was made to triple renewable energy globally and to double rates of energy efficiency improvements by 2030

- a fundamental gap in finance remains a major barrier to accelerating action. COP28 recognised the need for multitrillion-dollar investment to support the proposals

More specific to the UK, in the report CCC advocates various steps including:

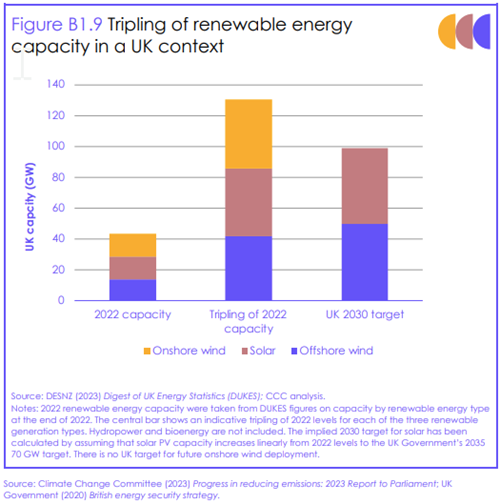

- a tripling of total renewable energy capacity (on 2022 levels) is due to be met or exceeded in UK offshore wind and solar PV respectively, as part of UK Government targets

- growth also in onshore wind. It is noted that meeting that overall target to triple renewables in the UK will require more significantly more onshore wind, despite there being no UK Government targets for the same.

This is strongly indicating that onshore wind is going to be critical in the policy jigsaw for the UK meeting COP28 aspirations and 2030 targets.

Planning reform in England and UK onshore wind

English Government planning policy for onshore wind is set out in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). The NPPF was amended in September last year which led to changes in the regime for onshore wind, including loosening of restrictions put in place in 2015. Onshore wind developments require planning permission and applications are determined by the Local Planning Authority (LPA) (rather than the Secretary of State, as is usual for major infrastructure projects). Under the old regime, wind developments could be quashed following a single objection; planning impacts on the community had to be "fully addressed"; and LPAs were banned from consenting to any new developments not included in the LPA's Local Plan.

Under the new regime, post-September 2023 reform, the Government allows LPAs to allocate new sites for wind via supplementary planning documents, in addition to the existing Local Plan method. Further, community planning concerns now need only be "appropriately" addressed rather than "fully addressed". Accordingly, new developments are better protected from minority local dissenters. Under the amended NPPF, LPAs are instructed to approve life-extending and "repowering" applications that replace and improve existing infrastructure. The UK government's reform to the onshore wind regime has eased restrictions, however, greater reform and opportunities for domestic and international developers lie ahead. In the context also of the CCC January 2024 report, the NPPF appears to be aligned with and supportive of the key next steps required in the UK.

Impact of regulatory change to date?

Whereas the loosening of restrictions should be beneficial for developers and investors in onshore wind, there has been questions about the impact of that regulatory reform. The Guardian newspaper had pointed out, in November and again in December last year, that there have been no new planning applications for new onshore turbines in England. This analysis is based on data from the UK Government' Renewable Energy Planning Database, which also shows a handful of applications in that period in Scotland and Wales combined, which both have a devolved planning regimes. So while there has only been a limited number of months since the NPPF amendments, that will be closely monitored in the months ahead, if the renewables targets and the CCC's next steps are to be met. Amidst all of this, this data over time is likely to show that onshore wind should have different trajectories of growth, depending on location and UK region. The science of it should simply dictate that onshore wind projects should aggregate where the conditions are best, subject only to connectivity to the grid and any other location-specifics. With the NPPF amendments however, there is clearly scope for further onshore wind across England, where appropriate, and the UK generally in support of UK government targets for renewable energy.

Election year

With a General Election in 2024, the political landscape is going to remain buoyant for renewable energy. The Government has been implementing policy and CCC has acknowledged that the Government's targets for offshore wind and solar are aimed at exceeding the COP28 aspirations. Opposition Labour's leader Sir Keir Starmer had stated that he wants to make Britain a "clean energy superpower" and onshore wind is Labour's number one energy policy priority. Both sides of politics can see that clean energy is a political imperative. Therefore a point of distinction may be in the intersection between fossil fuels and green energy. The UK Government had, in September last year, also been supportive of new investment in the carbon economy, with 27 new oil and gas licences granted late last year in the North Sea. That invited comment approaching criticism however by CCC that responded by advocating that "Strong, consistent domestic policy and communications on climate that avoid mixed messaging are crucial to be able to robustly advocate for high climate ambition internationally". Perhaps there will also be introduced into the political debate how the funding gap that COP28 referred to may be bridged – and whether the transitioning from fossil fuels may contribute to that. Other policy drivers might also come into play – the advantages of renewable energy for national energy security and also the subsisting trade gap in oil and gas. In particular, the UK Government's official statistics for UK trade show a net trade deficit of £49.2 billion last year in oil and gas, including £26.3 billion in gas and which partly supports the UK's gas-fired power generation, currently the biggest share of the energy generation matrix. That number looks remarkably similar to the £28 billion green investment fund initiative that is understood to soon be dropped by Labour. This only highlights the tensions between the imperative of carbon reduction and the financial costs of that transition. How that plays out in the election is likely to be pivotal to both main parties and it is arguable Labour's latest policy direction may similarly invite CCC comment, if and when appropriate.

Positive news

With that in mind and notwithstanding some of the challenges inherent in the 2030 targets, there is pause to celebrate overwhelming positive recent news for wind, both onshore and offshore, as well as renewables generally in the UK:

- RWE confirmed, at the beginning of January this year, start of construction of the onshore 63 MW Strathy Wood, in Caithness, in addition to the current construction of two other sites at Enoch Hill in East Ayrshire and Camster II in Caithness.

- RWE also acquired pre-Xmas three large offshore wind farm projects from Vattenfall: Norfolk Boreas (1.38 gigawatts) which had been put on pause by Vattenfall, as well as two other Vattenfall projects - Norfolk Vanguard East (1.38GW) and Norfolk Vanguard West (1.38GW);

- Ørsted also made its final investment decision on Hornsea 3 Offshore Wind Farm in the week before Xmas, which will be the world’s single largest offshore wind farm, with a capacity of 2.9 GW and due to be operational at end 2027; and

- On 21 December just passed, the UK hit a new record of wind energy production of 21.8 GW, providing 56% of Britain's electricity at the time. That percentage had itself been beaten on 19 November 2023, when wind met 69% of electricity generation.

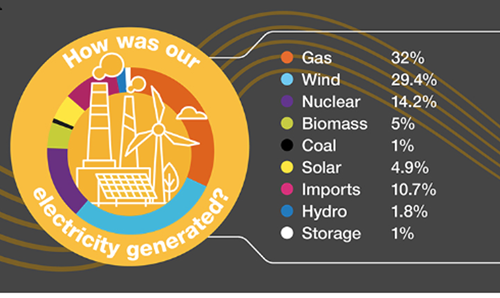

- The snapshot of energy mix is continuing to trend positively for renewables, with zero-carbon sources being greater than fossil-fuel for a sustained 15 months – or 5 consecutive quarters.

Source: National Grid ESO 9 January 2024

For the UK then, the next cycle of investment towards 2030 must involve more renewables, more wind and for that to involve new and ambitious targets for onshore wind being met. How will the table above in energy mix look then in 2, 4 and 6 years' time? Ambitious targets have been or need to be set and, by the swell of support, it is incumbent on government, industry and the nation to help deliver the same.

.png?as=0&dmc=0&iar=0&thn=0&udi=0?as=1&iar=1&mh=290&mw=290&hash=111A6FDE90B0B52FA04F2B0B8DDE770C&noindex=1)