- Home

- News & insights

- Insights

- EDPB guidance on dat…

- On this page

12 November 2020

Radar - November 2020 – 1 of 3 Insights

EDPB guidance on data transfers to third countries in wake of Schrems II

- In-depth analysis

What's the issue?

The CJEU judgment in Schrems II not only struck down the EU-US Privacy Shield, it also cast doubt on the future of data exports to the US and to other third countries which do not provide an adequate level of protection for the data. The CJEU said it was up to controllers to assess on a case by case basis, whether or not the data being exported would receive an equivalent level of protection to that in the EU, and to use supplementary measures to protect the data if it did not. Where any additional measures would still fail to ensure adequate protection, the transfer could not take place. No detail was provided as to what those supplementary measures might be and under what circumstances they would need to be used.

What's the development?

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has adopted recommendations on measures which may help supplement transfer tools to ensure personal data transferred to third countries is adequately protected. It has also adopted recommendations on the European Essential Guarantees for surveillance measures. The recommendations are subject to consultation and apply from publication.

The supplementary measures recommendations are intended to help data exporters comply with their duty to identify when supplementary measures are needed to protect data being exported to third countries outside the EEA which do not have an EU adequacy decision. They include a roadmap of steps needed to assess risk and select appropriate supplementary measures, as well as a non-exhaustive list of what those measures might entail.

The recommendations on the European Essential Guarantees for surveillance measures complement the other recommendations and provide exporters with elements to help them determine whether the legal framework governing public authorities' access to data for surveillance purposes in third countries can be regarded as justifiable interference which does not breach Article 46 GDPR.

The EDPB's guidance on this issue is the most authoritative pending any future court rulings, given that the EDPB is made up of Member State regulators. Organisations will also have to consider any guidance published by their own regulators, particularly in the UK given that the UK's ICO no longer sits on the EDPB. The ICO is, however, currently unlikely to diverge significantly from the EDPB and these guidelines will remain relevant to UK businesses exporting personal data to third countries after the end of the Brexit transition period unless we are told otherwise.

What does this mean for you?

While the EDPB outlines processes and optional supplementary measures to help make data exports lawful, it also warns that responsibility for assessment rests with data exporters who must proceed with "due diligence and document their process thoroughly". Even then the EDPB says it may not be possible to implement sufficient measures to allow a transfer to proceed and that there are no quick fixes or 'one size fits all' solutions. Organisations exporting personal data from the UK or EEA to third countries which do not have EU (or UK as the case may be) adequacy agreements will need to give the recommendations careful consideration against their exports on a case by case basis.

It may well be that risk cannot be sufficiently mitigated in which case the transfer must not go ahead and, if it is already happening, must be suspended. This will be disappointing news for exporters who continue to face the difficult task not only of assessing the level of adequacy provided by a third country, but of analysing whether or not there are steps to reduce risk to the data to a level which matches the European Essential Guarantees. It is certainly helpful to have the EDPB's views on the kinds of supplementary measures that may be effective but the recommendations fall some way short of providing certainty for exporters.

Exporters now need to ensure the EDPB's six-step plan is in place, and to pay particular attention to step 3 (assessment of level of protection) and step 4 (supplementary measures). Documenting the decision making process is essential.

Many organisations will already have started this process as most of the recommendations made by the EDPB are more or less as expected. However, perhaps the most striking element of this six step plan is the emphasis the EDPB places on objective assessment of the level of protection the data will receive in the third country. This should be done by reference to the laws of that country rather than in relation to the nature of the personal data and whether or not it is likely to be of interest to law enforcement authorities. One of the points made by the US Department of Commerce in its FAQs responding to the Schrems II judgment was that the majority of data transferred to the US is of no interest to the authorities and will not be accessed by them. This argument has been rejected by the EDPB as irrelevant. Those organisations which have been relying on the fact that the data they are exporting is not particularly sensitive and is unlikely to be of interest to public authorities, will need to think again.

Read more

Six steps to assess and address risk

The EDPB recommends following six steps in order to assess and mitigate risks associated with third country transfers:

- Know your transfers – map your data transfers, verifying that data transferred is adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which it is transferred and processed in the third country.

- Verify the transfer tool your transfer relies on – if you are relying on an EU adequacy decision, then the only obligation is to monitor its ongoing validity.

- Assess whether there is any law or practice of the third country that may affect the effectiveness of the appropriate safeguards in the transfer tools being relied on - this should be focused on relevant third country legislation, following the EDPB European Essential Guarantees recommendations (see below). Subjective factors such as the likelihood of the third country public authorities accessing the data being transferred in a manner not in line with EU standards should not be taken into account. The process should be done with due diligence and documented.

- Identify and adopt supplementary measures needed to bring the level of protection up to one equivalent to that provided in the EU - the EDPB makes recommendations as to what this might be in annex 2 of the recommendations (see below). If these are not sufficient, the transfer must be avoided or suspended. This process should be carried out with due diligence and documented.

- Take any formal procedural steps needed to adopt any required supplementary measures.

- Re-evaluate the level of protection given to the data and monitor developments which may affect it in line with the accountability process.

Assessing the adequacy of protection afforded to personal data in third countries

One of the most problematic issues for exporters is how to decide whether or not supplementary measures are required. The EDPB's recommended step three requires exporters to assess whether any law or practice in the relevant third country prevents the transferred data being adequately protected. To help exporters, in addition to the supplementary measures guidance, the EDPB has adopted recommendations on the European Essential Guarantees for surveillance measures. The EDPB summarises the elements needed to preserve EU privacy rights in four 'European Essential Guarantees':

- Processing should be based on clear, precise and accessible rules.

- Necessity and proportionality with regard to the legitimate objectives pursued need to be demonstrated.

- An independent oversight mechanism should exist.

- Effective remedies need to be available to the individual.

The guidance goes on to analyse what this means in the context of European jurisprudence and the EDPB also provides a brief list of resources in annex 3 of the supplementary measures recommendations but this falls short of a more useful analysis of country by country protections. The exception is in relation to the USA, The guidance states that if the data importer or any further recipient of the data falls under s702 FISA, then transfer tools can only be relied upon for the transfer if additional supplementary technical measures make access to the data transferred impossible or ineffective.

Given the EDPB's view that the nature of the data being exported is not relevant to the assessment of the level of protection afforded by a third country, it would be more useful for the EDPB to provide this analysis itself even though the CJEU places the responsibility for doing so on individual exporters.

What supplementary measures any help adequately protect transferred data?

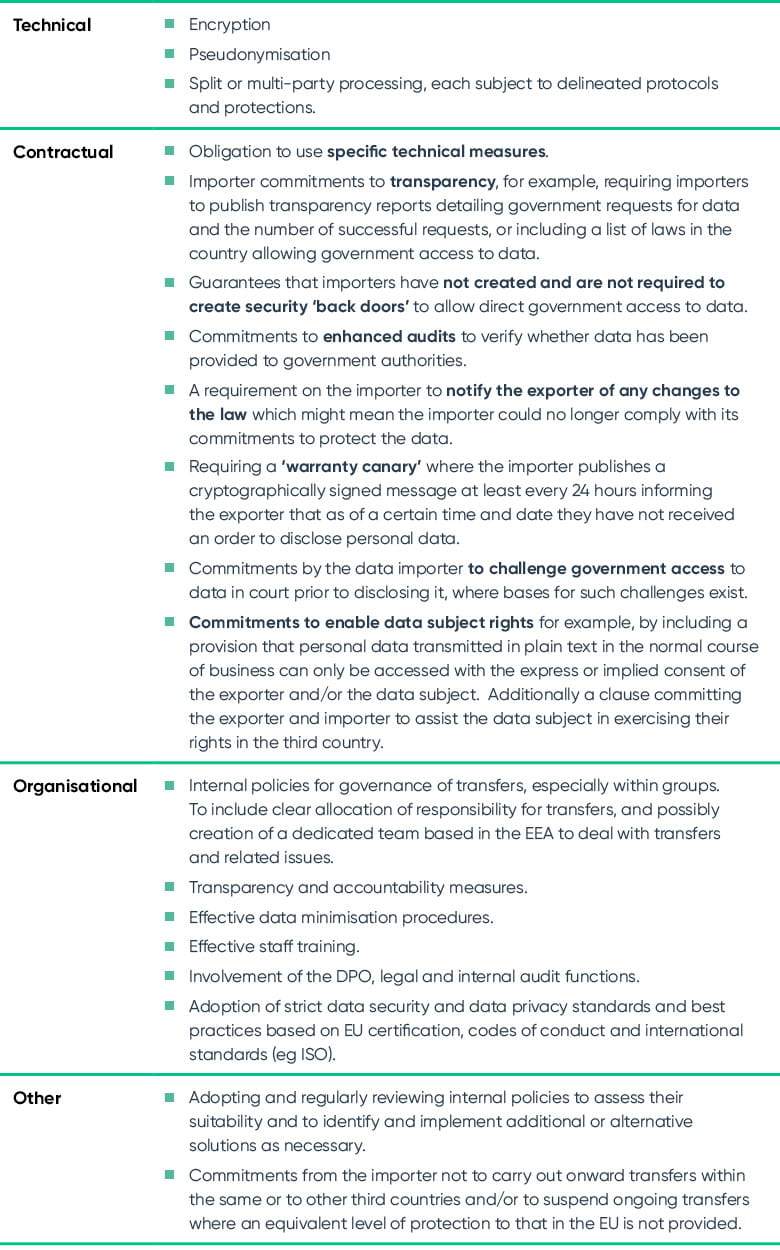

This is the element of the EDPB guidance everyone has been waiting for. If you decide that supplementary measures are needed to protect exported data, what are they and when will they be considered effective enough to allow the transfers to proceed? Annex 2 of the supplementary measures recommendations contains a non-exhaustive list of examples of measures which might lead to an effective guarantee that exported data will receive an equivalent level of protection to the one it enjoys in the EEA under EU law. These will not be universally effective and may need to be used in combination.

Both organisational and contractual measures must be used in conjunction with technical measures. In particular, contractual elements help complement and reinforce safeguards in transfer tools but the EDPB underlines that, as they are not binding on government authorities, they cannot by themselves remedy adequacy issues.

Examples of supplementary measures

Which measures should be used when?

The following factors should be taken into account when identifying supplementary measures to adopt:

- Format of the data to be transferred (i.e. in plain text/pseudonymised or encrypted).

- Nature of the data.

- Length and complexity of data processing workflow, number of actors involved in the processing, and the relationship between them.

- The possibility that the data may be subject to onward transfers within or to other third countries

The EDPB recommendations provide specific use cases for types of technical measures and the EDPB stresses that the recommended measure may not be effective if used in a different context to the one provided by way of example in the recommendations.

When will supplementary technical measures fail to sufficiently increase protection?

There are also two examples of situations in which there will be no appropriate technical safeguards available should the third country not provide an equivalent level of protection. These are unencrypted processing (processing in the clear) by cloud service providers, and remote access and use of unencrypted data by a third country importer for business purposes including human resources processing. This will be the case even where both transport encryption and data-at-rest encryption are used.

Now the task of applying these guidelines to individual export operations can begin in earnest, even for organisations which have already put elements of them into action.

In this series

EDPB guidance on data transfers to third countries in wake of Schrems II

12 November 2020

EC set to tackle regulating the digital environment

16 November 2020

Related Insights

Data and cyber security - 2025 roundup