- Accueil

- Actualités et public…

- Publications

- Supreme Court clarif…

- Sur cette page

28 janvier 2026

Case law in the construction industry – 4 de 5 Publications

Supreme Court clarifies JCT termination rights

- Quick read

In the case of Providence Building Services Ltd v Hexagon Housing Association Ltd [2026] UKSC 1, the Supreme Court has provided important clarification on the interpretation of termination clause 8.9.4 in the standard form JCT Design and Build Contract 2016 edition (JCT D&B 2016) (which continues to be used in the standard form JCT Design and Build Contract 2024 edition (JCT D&B 2024)).

The background

The employer and the contactor entered into a building contract incorporating the JCT D&B 2016, subject to certain bespoke amendments, for construction works in Purley, London for approximately £7.2 million.

Clause 8.9 of the building contract set out the following points, relevant to the case:

- 8.9.1: if the employer fails to pay the amount due to the contractor by the final date for payment, the contractor may serve a notice of specified default to the employer.

- 8.9.3: if the specified default continues for 28 days from receipt of the notice of specified default, the contractor may, on or within 21 days from the expiry of the 28 day period, by further notice to the employer terminate the building contract.

- 8.9.4: if the contractor for any reason does not give the further notice in clause 8.9.3 but (whether previously repeated or not) the employer repeats a specified default, then upon or within 28 days after such repetition, the contractor may terminate the building contract with notice to the employer.

The issue arose in relation to two payment rounds where the employer failed to pay the sum due by the final date of payment. The first was in December 2022, where the contractor served a notice of specified default pursuant to clause 8.9.1. However, the employer paid the amount due so that no right to terminate under clause 8.9.3 accrued. The second was in May 2023, where the contractor issued a notice of termination pursuant to clause 8.9.4 the day after the employer failed to pay the sum due, arguing that this was a repetition of the specified default from December 2022.

The dispute

The question to be answered was: can a contractor terminate under clause 8.9.4 for a repeated specified default without having previously accrued a right to terminate under clause 8.9.3? The employer argued no and that the contractor had repudiated the building contract by terminating under clause 8.9.4 and referred to the dispute to an adjudicator. The adjudicator largely found in the employer's favour, and as did the High Court. This decision was reversed by the Court of Appeal, who found in the contractor's favour. However, the Supreme Court then allowed the employer's appeal.

The decision

The Supreme Court concluded that for a contractor to serve a termination notice under clause 8.9.4, the contractor must have previously accrued a right to serve a termination notice under clause 8.9.3.

The opening words of clause 8.9.4 that refer to clause 8.9.3 demonstrate that clause 8.9.4 is dependent on clause 8.9.3. If employer repetition of a specified default was sufficient for a contractor to terminate under clause 8.9.4, clause 8.9.4 would simply start with "If the Employer repeats a specified default….".

The Supreme Court's interpretation of the clauses also produces a rational and less extreme outcome than the alternative, preventing "a sledgehammer to crack a nut" scenario where two payments, each one day late, could trigger termination. Employers shouldn't have to rely on clause 8.2.1 (that termination should not be given unreasonably or vexatiously) for protection in such instances.

The takeaways

Contractual interpretation of standard form contracts

When looking at how to interpret a standard form contract like the JCT, the Supreme Court considered that the court is more likely to focus its attention on the background generally known to participants in the industry (and not the background known to the individual parties to a particular transaction). However, in saying this, the court made clear that it was not dismissing the usual contractual interpretation approach of looking at the objective intentions of the parties in the relevant context; as the court said that the objective intentions of parties using standard form contracts would be presumed to reflect the intentions of those who drafted the standard form contracts, subject to any bespoke amendments.

Contractor cashflow

Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal considered the relevance of methods available to a contractor to protect its cash flow position when looking at the interpretation of clause 8.9.4. However, the Supreme Court held that any contractor cash flow difficulties and methods to combat them should not distort contractual interpretation. If the termination clauses in the JCT inadequately protect contractors in this area, this is a matter for the JCT to address in future editions and not for courts to remedy through interpretation.

Symmetry between an employer and a contractor

The Supreme Court confirmed that there is no requirement for symmetrical termination rights between an employer and a contractor, given their fundamentally different obligations. Clause 8.4.3 (employer's right to termination) of the JCT D&B 2016 intentionally supports this; in contrast to clause 8.9.4, clause 8.4.3 does not require a previously accrued right to terminate.

The implications in practice

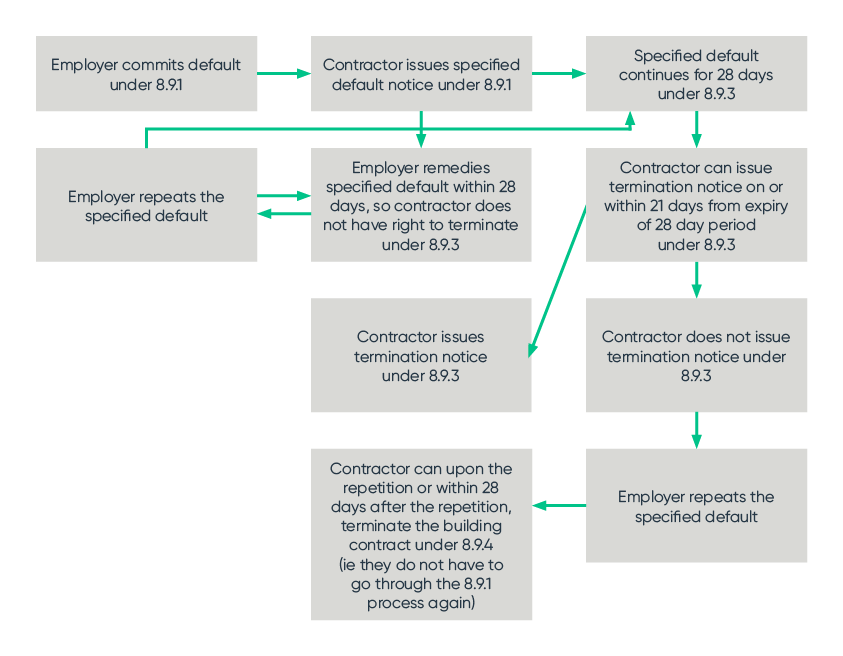

Given the JCT D&B 2024 continues to utilise the same termination clauses ruled on by the Supreme Court, this decision will have relevance for construction projects now and going forwards. It is a reminder to employers to ensure rigorous payment compliance, but a warning to contractors that repeated non-payment by an employer will not always result in a "fast track" to termination. How clause 8.9 works in practice on the facts of the case can be demonstrated in the following diagram:

The Supreme Court decision also emphasises some clear general principles of contractual interpretation, particularly in industries where standard form contracts are routinely deployed. In the construction industry, these principles may not only apply to the JCT suite, but also to other suites of standard form contracts such as NEC4 and FIDIC.

For example, all parties and practitioners involved in the negotiation process of construction contracts must take care so that any bespoke amendments agreed between the parties have the desired result, particularly if contradictory to the objective intention of the relevant provisions in the standard form.

We also have good authority that where a reference to one clause is inserted into another, this can be interpreted as a "gateway" that inextricably links the two clauses together and can result in one being conditional on the other. This will need to be kept in mind if parties intend certain provisions to be independent.

Final thoughts

Ultimately, this judgment makes welcomed sense of clause 8.9 in the JCT D&B 2016 and more broadly, it serves as a valuable reminder for construction parties that careful attention to both the wording and the structure of clauses – and the way in which they interact with one another – is critical. This is both to ensure that parties' intentions have been documented and to avoid disputes arising in the future.

Dans cette série

A question of fine balance: does an assignee have the right to adjudicate?

19 février 2026

Roundup of payment case law in the construction industry in 2025

13 février 2026

par Sophia Yew, Emma Coates

Vista Tower Appeal: Upper Tribunal Provides Guidance on RCOs

5 février 2026

par Emma Coates

Supreme Court clarifies JCT termination rights

28 janvier 2026

par plusieurs auteurs

Building safety: roundup of case law in 2025 and what to look out for in 2026

4 décembre 2025

par Rebecca May, Emma Coates

Related Insights

A question of fine balance: does an assignee have the right to adjudicate?

par Kourosh Abelehkoob et Emma Coates

Roundup of payment case law in the construction industry in 2025

par Sophia Yew et Emma Coates

Vista Tower Appeal: Upper Tribunal Provides Guidance on RCOs

par Emma Coates