- Accueil

- Actualités et public…

- Publications

- key design developme…

- Sur cette page

14 janvier 2025

Brands Update - January 2025 – 2 de 3 Publications

In case you missed it - key design developments in 2024

- In-depth analysis

Our round up of the key design law related developments in 2024. Our round up of the key trade mark developments is here.

Court of Appeal clarifies UK design law in Aldi gin bottle case

The Court of Appeal has confirmed that the design of Aldi's light up festive gin-based liqueur, sold during Christmas 2021, infringes Marks & Spencer's (M&S's) registered designs for a similar bottle. As well as illustrating the potential benefits of having an 'arsenal' of IP rights in place for products and packaging, the decision is also significant in that it clarifies a number of areas of design law that were somewhat unclear.

In particular, the Court held that products manufactured to – and product indications associated with - a registered design can be used to help resolve any ambiguities as to what is shown in a design image for a registered design. In addition, designs disclosed by the design owner during the 12-month grace period are to be excluded when assessing infringement (as well as validity) of the registered design but only if they do not form a different overall impression to the design in question. This means that design owners need to be careful when testing out different designs or using similar designs for different products on the market. For more, see here.

| Prior registration | Allegedly infringing design |

|---|---|

|

|

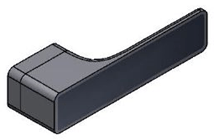

Informed user more observant than average consumer and ease of use is relevant for overall impression

In the M&T door handle case, the EU General Court confirmed that the informed user is not a sectoral expert or a professional linked to the product in question (eg a handle salesperson). The informed user is more observant than the average consumer in trade mark law but they are not an expert. Given that the informed user is particularly observant, he or she is capable of observing in detail the minimal differences that may exists between the designs at issue.

The overall impression of a product is assessed based on its visible features. The importance of the visible features of the product are assessed on the basis of their impact not only on the product's appearance, but also on the ease with which the product can be used.

In the present case, the rounded and thinner shape of the edges of the contested design (see below) would influence the manipulation of the handle and its ease of use. Those elements would be perceived by the informed user and therefore are not marginal. It means that the contested design created a different overall impression on the informed user. The case emphasises that ease of use as well as appearance affect overall impression.

| Prior art | Contested design |

|---|---|

|

|

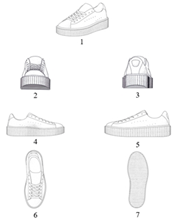

Instagram posts sufficient to demonstrate prior disclosure of design

In Puma v Rihanna, the EU General Court clarified that the applicant for a declaration of invalidity is free to choose the evidence that they think will best support the invalidation request. If some evidence, on its own, is insufficient to prove the disclosure, the same piece of evidence may contribute to establish disclosure when combined or read in conjunction with other documents or information. For example, it was noted that shoes sold in a pair are usually uniform so there is no reason to infer that the right shoe was different from the left shoe. It is also worth noting that what matters is the evidence filed at the EUIPO and not the versions (with possible reduced quality) contained in the contested decision or in the written pleadings of the parties.

In the present case, the Court was satisfied that the Instagram posts submitted by the applicant showing Rihanna wearing white trainers were of sufficient quality to allow all the features of the prior (novelty destroying) design to be recognised. The Court also noted that there was no factual basis to doubt that the photos in questions originated from Rihanna's own Instagram account. Given that Rihanna was a world-famous pop start at the relevant date, it was reasonable to believe that not an insignificant proportion of her followers looked at the photos with particular interest in order to identify what she was wearing. Given that the photos were published 12 months before the filing of the design application, the grace period did not apply and the design was invalid for lack of novelty. This decision illustrates the risk of self-disclosure, particularly online.

| Prior art | Contested design |

|---|---|

|

|

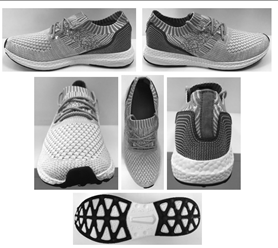

Disclaimed features of earlier design can be taken into account when assessing individual character of later design

In Puma v EUIPO/Road Star Group, the EU General Court confirmed that all the elements protected by a contested design must be taken into account in comparing the overall impression it creates compared to prior disclosures. This is because it is necessary to establish if the contested design, in its entirety, satisfies the requirements for protection over the prior art.

In the present case, the question was whether the sole of a design for a contested shoe was a dominant feature such that the shoe as a whole would create a similar overall impression to a prior disclosure of a shoe with a similar sole. The Court held that it was not a dominant feature. Therefore, the assessment of the overall impression could not be dominated by the appearance of the sole.

The Court also clarified that the function of the prior art is to reveal the status of earlier designs relating to the product in question. Therefore, it is not necessary to limit the assessment to features of the prior art which are themselves protected as designs - disclaimed elements of a prior design can also be taken into account in assessing whether a later design creates a different overall impression.

Given the above, the contested design was found to create a different overall impression compared to the prior art, an example of which is depicted below. The case illustrates the need to compare the contested design to all elements of prior designs that have been disclosed.

| Prior art | Contested design |

|---|---|

|

|

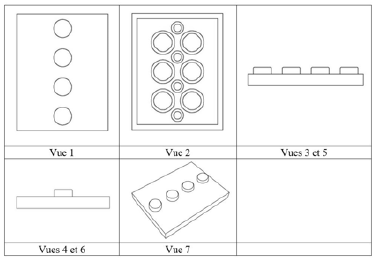

All characteristics of design must be solely dictated by technical function for invalidity

In Lego v EUIPO/Delta Sport Handelskontor, the EU General Court confirmed that a design will be declared invalid only if all of its characteristics are solely dictated by their technical function. If at least one feature is deemed to be not solely dictated by its technical function, the design remains valid. In the present case, the smooth surface of the upper face of the toy brick was not solely dictated by its technical function and so the registration was valid.

Likewise, the design did not foul of the must fit exclusion since this provision does not apply to modular designs, provided they are new and have individual character. The Board of Appeal had already held that the design of the Lego brick met the definition of a modular design. Since the applicant for invalidity had failed to supply any evidence that the Lego brick design was not new and/or did not have individual character, it could not show that it was deprived of protection as a modular design. It is for the invalidity applicant (not the owner of the design) to submit this evidence as it is difficult (if not impossible) for the owner of the design to prove a negative (ie that there is no prior art that is novelty destroying or which creates the same overall impression on the informed user).

In addition, the Court clarified that the disclosure of an earlier design is a question of fact which must be proved on a case-by-case basis. The applicant for invalidity cannot rely on it being a well-known fact that a particular prior design has been disclosed to the public.

This decision clarifies that the burden of proof in invalidation proceedings is on the cancellation applicant who must adduce concrete evidence capable of demonstrating the disclosure of the earlier design (for example, mere website links are not sufficient). The decision also confirms that the presumption that a registered design is valid also applies to modular systems.

Designs can protect some works of applied art

In the UK, the High Court has recently acknowledged in the WaterRower v Liking decision that, in relation to works of applied art, there is an insurmountable conflict between the EU test for copyright protection and the UK's statutory test. It means that copyright protection for such works (at least for the time being) in the UK is difficult. The position is different in the EU.

While trade mark protection for product shapes is possible, obtaining such protection can often be complex. Relying on registered designs is a cost-effective alternative although registration only lasts for a maximum of 25 years and the design must be registered within 12-months of first disclosure.

Nonetheless, in appropriate cases, design protection is merited and can lead to successful enforcement (see eg here). In the EU, there are some interesting cases in the pipeline relating to design protection for works of applied art, such as the pending USM Haller and Deity Shoes ECJ cases.

New EU design package published in the Official Journal

The new EU Design legislation was published on 18 November 2024 in the Official Journal of the European Union. The Directive will enter into force on 8 December 2024 and Member States will have 36 months to transpose it into their national law. The Regulation will also enter into force on 8 December 2024. Most of the articles will apply from 1 May 2025. However, some provisions require implementation through secondary legislation so they will apply from 1 July 2026. For more on the EU reform, see our article here.

UK and EU law on designs will (partly) diverge once the reforms are in place. However, the UK has indicated that it will conduct a consultation on the UK design regime in 2025. It is hoped that – like the EU - the UK expands the definition of 'design' and 'product' so that they encompass such things as virtual designs and products. It is also hoped that the UK provides greater clarity on the acceptance of representations of animated designs (including graphical user interfaces) which have been problematic post-Brexit.

Riyadh Design Law Treaty adopted by WIPO members

WIPO Member States adopted the Riyadh Design Law Treaty (DLT) on 22 November 2024. The DLT aims to streamline the formalities associated with applications for the protection of industrial designs (but not the substantive law). The Treaty requires 15 contracting parties to agree for it to enter into force. Various papers on the DLT can be found here and the press release is here.

One particularly useful aspect of the Treaty is a consistent 12-month grace period for designers to publicly disclose their designs without losing the right to register those designs. This grace period allows designers to test their designs in the market and receive feedback before seeking protection. Not all WIPO members currently offer such a period (or such a long period).

Dans cette série

In case you missed it – key trade mark developments in 2024

14 janvier 2025

par Louise Popple

In case you missed it - key design developments in 2024

14 janvier 2025

What's on the horizon for brands? A look forward into 2025

14 janvier 2025

par Louise Popple

Related Insights

The case all marketing teams should read - Dryrobe v Caesr Group

par Louise Popple

When laudatory marks are given broad protection: Sexy Fish

par Christian Durr et Louise Popple

easyGroup v Premier Inn: Court rejects family of marks monopoly and clarifies section 10(3) protection

par Louise Popple et Moira Sy